The Role of War Veterans in Zimbabwe’s Political and Economic Processes

Paper presented by Wilfred Mhanda to the SAPES Trust Policy Dialogue Forum in Harare on 7 April 2011. Wilfred Mhanda, aka Dzinashe Machinugura, was a commander of the Zimbabwe People’s Army (Zipa), and in the leadership of the alternative Zimbabwe Liberators Platform.

Zimbabwe’s former liberation fighters have become a household name for all the wrong reasons. This paper will seek to trace the development of the role of war veterans in Zimbabwe’s political and economic processes particularly from 1997 onwards to date and provide a contextual background for their perceived role and put the public perception of the former fighters in perspective.

The war veterans came into being with the demobilisation of those former ZIPRA and ZANLA fighters who were not attested into the Zimbabwe National Army, ZNA in 1980. The advent of Zimbabwe’s independence on 18 April 1980 and the subsequent formation of the Zimbabwe National Army made the former liberation armies both superfluous and redundant as their mission of liberating Zimbabwe had been accomplished. ZIPRA and ZANLA no longer had any role to play in an independent Zimbabwe. From then onwards, we could only refer to former ZANLA and former ZIPRA fighters. It is these fighters who then became referred to as veterans of the national liberation war. Maintaining the ZIPRA/ZANLA labels and their links to the liberation parties would have only served to undermine the unity and cohesion of the new army as evidenced by the counter-productive ZANLA/ZIPRA clashes in places like Entumbane in 1980/81.

The former fighters were weaned off from their parent political parties ZANU and ZAPU and their welfare became the responsibility of the new Government of Zimbabwe and not of their former mother parties. Any links with the political parties could only now continue in terms of individual membership of those political parties. It is instructive to note that, technically, the overwhelming majority of the former fighters were never card carrying members of the political parties ZANU and ZAPU that parented ZALNLA and ZIPRA; nor were they required to do so. They became registered members of the parties’ armed wings and not the parties. All that was required of them was the commitment to fight for the liberation of their country. For the fighters on the other hand, the political parties and their armed wings became vehicles and instruments for the liberation of Zimbabwe.

Indeed, the former fighters had both political and economic roles during the liberation war in addition to their fighting role. The liberation armies were simultaneously a fighting, political and economic force. Their role as a fighting force entailed waging war against the illegal racist, minority Smith regime to inflict defeat on them. Their role as political force encompassed fighting for democracy, self-determination and liberation and mobilisation and organisation of the masses of the people to support the liberation war as their war; a people’s war that could only be won by fully mobilising the people and relying on them. The economic role of the liberation forces was determined by their engagement in production related activities to sustain themselves. They hoped for external assistance but principally they were dependent on their own efforts which underpinned the concept of self-reliance. Furthermore, fighting the enemy did not only entail engaging his forces but the destruction of the economic base supporting his war effort like road, rail and communication infrastructure and the disruption of agricultural and farming activities. This was another economic role of the liberation armies; the destruction of the enemy’s economic lifeline to complement the United Nations economic embargo imposed on Rhodesia after UDI.

The period from 1980 to 1990 could be characterised as a phase of dormancy for the former fighters as they tried to adjust to the new reality of finding their way back into society. This was a very crucial period as it planted the seeds of some of the problems associated with the former fighters that surfaced almost two decades later, as the chickens came back home to roost. It is generally accepted that in post-conflict situations, there is a need to provide for equitable, sustainable assistance to veterans as part of their disarmament, demobilisation and re-integration into society. Failure to do so invariably leads to instability engendered by the disaffected veterans. Indeed, the ZANU-PF government has been castigated by independent researchers and analysts for failing to adopt a sound veterans’ policy for their re-integration back into society. They have also decried the initial efforts at demobilisation in 1981 as inadequate.

According to A.G. Dzinesa:

…no elaborate reintegration policy was designed, besides the provision of a grant of $400. The opportunity to plan a comprehensive DDR strategy at the earliest possible stage was lost. The limited reintegration strategy resulted in ineffective integration of these demobilised combatants, the majority of whom registered under the demobilisation Programme of 1981 .[1]

Gerald Mazarire and Martin Rupiya concur:

Given the impact of resources at the individual level, set at Z$185,00 per month over 24 months, the sums were generally far short of what was required to adequately assist former combatants to ease themselves back into the capitalist economy inherited from Rhodesia. Many lacked the necessary skills while those in command of the economy spurned the new entrants. Furthermore, serious government corruption was later unearthed in the selection and allocation of scholarships. As a result, these did not really benefit the intended beneficiaries – the ex-combatants. [2]

Muchaparara Musemwa adds:

The government’s demobilisation package which in the words of an ex-guerrilla Albert Nyathi was a ‘pitiful alternative to Operation Seed ‘, is in fact ‘notorious’ for falling far short of adequately preparing ex-combatants to returning to civilian society. It was an impetuously designed programme that overlooked the diverse socio-economic needs of each and every demobilised ex-combatant. Very little if anything was done to assess the extent to which society at large was prepared to absorb them. Some ex-combatants had practical problems like not having a place they could call home … [3]

According to Dzinesa:

Notwithstanding the existence of a dedicated Demobilisation Directorate, there were programmatic and institutional gaps. These included a lack of broad and consistent socio-economic profiling of combatants, the failure to implement financial management skills training for the many ex-combatants inexperienced in handling (demobilisation) money, incompetent and corrupt directorate staff, an absence of elaborate and workable business or cooperative support mechanisms and the lack of proactive monitoring mechanism. The majority of the ex-combatants enterprises collapsed due to these factors while agro-based enterprises were also hard-hit by drought. [4]

The same conclusions were also reached by Musemwa. [5]

It is instructive to note that the problems of violence, anarchy and lawlessness that Zimbabwe associated with war veterans from 1997 onwards can be attributed to the failure by the government, society and the donors to implement a sound, sustainable policy of demobilisation, catering for the welfare of the former fighters and facilitating their reintegration into society.

It is also noteworthy that the former liberation parties, ZAPU and ZANU were notable by their silence as the former liberation fighters struggled to find their feet in the new Zimbabwe that they fought so hard to bring about. War is a very excruciating and traumatic experience and the first thing that should have been addressed ahead of any financial and material benefits, was to facilitate the former fighters’ re-integration into society through providing counselling to help them cope with post traumatic stress disorders. Sadly this was never done.

The first decade into independence saw the former fighters slide into extreme poverty and destitution. They were so to speak, war veterans in themselves. It was this desperate situation and misery that saw them form the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association, ZNLWA as a vehicle to champion their forgotten interests. With the formation of the association in 1990, with Justice Charles Hungwe as the founding chair, the fighters transformed from being war veterans in themselves to become war veterans for themselves. It was against a lot of resistance that the association was formed as both the political and bureaucratic establishment were apprehensive about the move, with most of them not being former fighters. They feared that the new association could de-legitimise them on that account. The war veterans association was registered as a non-partisan membership organisation in terms of the Private Voluntary Organisations Act to cater for the welfare needs of the former fighters. It was not a case of all former fighters automatically becoming members of the organisation. Some of the actions that were later associated with the organisations are clearly inconsistent with the provisions of the Act and could easily be used as arguments for its de-registration.

The government responded with the enactment of the War Veterans Act two years later to cater for the welfare of the former fighters in a desperate effort to contain the reach of the new organisation. The Act was meant:

to provide for the establishment of schemes for the provision of assistance to war veterans and their dependants; to provide for the establishment of a fund to finance such assistance; to provide for the constitution and functions of the War Veterans Board; and to provide for matters incidental to or connected with the foregoing (War Veterans Act: Chapter 11:15, 1996).

These were indeed very altruistic and well-meaning objectives that could have gone a long way to uplift the former fighters and mitigate their miserable plight. But for the record, other than the formation of a War Veterans Board and the creation of a dedicated ministry nothing came of the Act’s noble intentions. The former fighters had to take to the streets five years later to get any form of assistance despite the clear provisions of the Act.

The country’s former liberation fighters hit the headlines in the in the years 1996-97 in connection with compensation payments based on War Victims Compensation Act that had been on the statute books since the time of the Rhodesian war against the guerrillas. The Victims of Terrorism (Compensation) Act of 1973 was introduced by the Smith regime to compensate for death, injury and damage or loss of property caused by an act of terrorism on or after 1972. [7] At independence, the Act was amended to include almost all who could have been negatively affected by the war be it in education or loss of income. The beginning and cut off period was set at March 1962 to March 1980. [8] Under the War Victims Act, injury means ill health, physical and mental incapacitation caused by war inside Zimbabwe and in the neighbouring countries between 23 December 1972 and 29 February 1980. [9] The ZANU-PF government established a War Victims Compensation Fund in 1980 for payments to victims in terms of the Act. As noted in the previous sentence, the majority of the former fighters were eligible for compensation in terms of the broad provisions of the Act. However the rank and file of the former fighters were not aware of its existence and provisions. The politicians, on the other hand, had drawn benefits from it. According to the weekly Zimbabwe Independent publication of 17 May 1996, with the column heading ‘Chefs help themselves to war veterans compensation fund’:

Top politicians, senior government officials and other influential people in Zimbabwe’s liberation war have allegedly drained the national fiscus of millions of dollars through inflated compensation claims for disabilities they say they sustained during the struggle.

Operatives in the pension’s office, most of them war veterans themselves, observed who was benefitting. Word soon got around in 1995 that the former fighters could submit applications for compensation for various claims. A flood of applications followed. These were processed by the relevant department in the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare. Initially a number of medical practitioners made the disability or injury assessments but subsequently it was Dr Chenjerai Hitler Hunzvi [10], then stationed at Harare Central Hospital, who took it upon himself to do the bulk of medical evaluations.

Queues of up to 500 fighters could be seen for weeks at the War Veterans Association HQ in Belgravia. The rank and file former fighters started drawing compensation from the fund in 1995 i.e. two years before the alarm was raised that the fund had been looted by the former fighters, primarily service chiefs, senior army commanders and civil servants. It was the Zimbabwe Independent which first exposed the scam in 1996. [11] Compensation payments were stopped in April 1997 following a public outcry. According to The HERALD of 18 April 1997:

The unexpected high figure, age of some of the claimants and purported beneficiaries and alleged abuses of the War Victims Compensation Fund recently led the Government to suspend further disbursements of funds under the facility and order investigations into the allegations and come up with a water tight policy on who should qualify.

The government subsequently established a commission of inquiry headed by then Judge President Justice Chidyausiku a couple of months later in 1997. Senior commanders and prominent fighters were paraded before it in a humiliating fashion to answer for their compensation awards and vouch for their disability.

According to the Herald report of 18 April, Minister of Public Service, Labour and Child Welfare, about 70 000 compensation applications had been processed, with a possibility of rising to 100 000. It is highly improbable that more than 20 000 former fighters had benefited from the fund by the time it was stopped. Besides, also according to the same issue of the Herald:

Whilst mostly former combatants are among the list of those who have benefited from the fund, former Rhodesian soldiers are also drawing from the fund which does not restrict it to former Zipra and Zanla combatants only as is now commonly believed.

Also in the same HERALD issue, Minister Chitauro commenting on the magnitude of the figure of beneficiaries says:

The figures were astronomical given that about 35 000 former Zanla and Zipra forces were demobolised in 1980 while the war veterans registers had even less.

Furthermore, the same HERALD issue under the headline ‘ 23-year-olds among war fund claimants’ quoted Minister Chitauro:

There were reported cases of 23 year-olds applying for compensation yet these should have been toddlers when the war of liberation was being waged in the country. “The youngest person to qualify should be around 33 t0 35 years old” she said.

The HERALD issue of 6 June 1997 also carried a report of a fraudster Lovemore Nyirenda who swindled the Pensions Office of Z$ 400 000 from unlawful claims from the War Victims Fund and was convicted of fraud by a Harare magistrates court.

All these foregoing factors suggest that the former fighters could not have been the major beneficiaries of the War Victims Compensation Fund although public perception suggested otherwise. This led the former fighters to conclude that they were victims of a deliberate campaign to target them for smearing. The Financial Gazette issue of 26 August 1997 carried a headline in its National Report of ‘Ex-combabtants cry foul as ernquiry unfolds – We are being made sacrificial lambs”:

Former freedom fighters in Zimbabwe’s war of liberation testifying before the presidentially-appointed commission charge that there are attempts by “hidden hands” in the top echelons of the party and the government to use them as fodder in the crisis surrounding allegations that the fund was looted of millions of dollars by top politicians and others in Zimbabwe .

“The is something wrong if we now must appear before a commission to explain why we were compensated for our injuries, while the real looters of the fund remained unscathed by the investigation” said Rushesha, now Minister of State for Gender issues. .. “We see a deliberate ploy to embarrass comrades yet there are people in the party and government who bought apartments in Harare and additional farms through the War Victims Fund but these people are not being hauled before this commission”: she added.

Her testimony and emotions dovetailed those of other ex-combatants highly active during the war who have appeared before the commission which enters its seventh day..

Chris Mutsvangwa, a former detachment commander with ZANLA forces, the armed military wing of ZANU PF during the liberation war said: “There is no doubt that this commission’s hearings are exposing what many of us who participated in the war have always known: the welfare of the ex-combatants was never on their priority list.. They were too busy lining their pockets to care about us.” He said it was unfair that ex-combatants continued to line up before the commission while ‘the real people with a case to answer continue to live in opulence and ridicule the lives of the ex-fighters.

Not all the fighters benefited as the payouts were abruptly halted with charges that the former fighters had looted the fund. [12] This development raised tensions between the war veterans and the state, as the former felt they were being used as a smoke-screen to disguise the looting that had earlier occurred by politicians and others who had been nowhere near the war. In addition, to many war veterans, the Chidyausiku Commission, established less than two months after the compensation payments had been suspended, was merely a device to discredit them.

The animosity between the war veterans and politicians was not something new. Norma Kriger has explored the differences between the two groups over state assistance to war veterans and state pensions for heroes. She based her study on excerpts from debates in Zimbabwe’s Parliament. Kriger refers to the lamentations of excombatants:

Excombatant MPs saw ‘the enemy’ as being within the government and the ruling party – the associates of Bishop Muzorewa and Ndabaningi Sithole, and the cabinet ministers who had advanced their education during the war. One excombatant said that some representatives left the House or went to drink tea when the House was going to debate ex-combatants. In 1980 some of these people were already ‘sitting pretty’ – they owned farms, supermarkets and so forth. ‘These same people do not like to see ex combatants near them. Some were working closely with Muzorewa and now they do not want ex-combabtants near them’ [13]

It is noteworthy that all the nationalist detainees who either died in detention before independence or were murdered by the Smith regime were recognised as heroes for their contribution to the struggle whereas those captured guerrillas that were executed by the regime have their remains still lying in prison cemeteries like Chikurubi without being either rehabilitated or recognised as heroes . [14]

The war victims’ compensation fund saga went a long way towards creating negative public perception of the former fighters and they never fully recovered their honour after this episode where they felt they were made scapegoats.

Their continuing miserable plight pushed the war veterans association in 1997 (now under the leadership of Chenjerai Hitler Hunzvi as national chairman) to demand for pensions and other related benefits from the state. President Mugabe finally succumbed to the demands of the former fighters, after facing unprecedented humiliation by the leadership of the former fighters. He undertook to make lump-sum payments of Z$50,000 (USD4000) to all the former fighters and agreed to pay them Z$2000 (US$150) monthly pensions; provisions for health, education and burial were also agreed. It has to be said that President Mugabe had his back against the wall when he acceded to the war veterans’ demands in the face of unrelenting and humiliating demonstrations against the government that the police did nothing to stop. The grants and pensions had not been budgeted for, thus throwing the fiscus off balance. Soon after the payouts to the veterans, the Zimbabwe dollar crashed on 13 November, 1997 losing its value to the American Dollar by 73 per cent thereby eroding the value of the payments and nullifying the intended benefit. [15]

There was a subsequent public outcry against the war veterans blaming them for crashing the economy. Most economists and analysts trace the economic slide down to the war veterans’ gratuities payments despite the rampant corruption within the state parastatals that ran into billions of Zimbabwe dollars and the DRC war that was consuming up to one million United States Dollars per day. There is need to put the payments in context. All countries that fought for liberation, resistance or patriotic wars have a special place for their heroes and heroines in both their institutional memory and their national history just as we hold Mbuya Nehanda, Lobengula, Sekuru Kaguvi and others in eternal esteem for their sacrifices. This is generally expressed in material and other forms of genuine appreciation. The material acknowledgement in the form of pensions, farms, residential stands etc that former Rhodesian soldiers, black and white, received from the British Empire for fighting its wars, is living testimony for this. To this end, the former fighters need neither be ashamed of nor be derided for what others elsewhere would ordinarily deserve or enjoy.

Hunzvi had been elected national chairman of ZNLWA in 1997. However one year later he was deposed by his executive, which passed a unanimous vote of no confidence in him for his authoritarian leadership style and allegations of corruption involving the embezzlement of the association’s investment companies’ funds. The companies were formed through the pooling of funds from the war veterans’ gratuities. His deputy was Moffat Marashwa with Cosmas Gonese as the association’s secretary general. Hunzvi did not accept his removal but did not contest it with the executive. Instead, he set up an alternative executive with Patrick Nyaruwata as his deputy. For the first time we had men appearing in the national executive such as Douglas Mahiya, Andy Mhlanga, Mike Moyo, Andrew Ndlovu and Joseph Chinotimba, whose junior status during the war gave them no authority to speak on behalf of the war veterans,. Mahiya, Mhlanga and Moyo had been in the Harare provincial leadership of the association. In early 1999, Hunzvi’s new executive split up again amid allegations of the embezzlement of funds of the association’s investment companies like ZEXCOM. Nyaruwata became the leader of one of the factions supported by Mahiya, Mhlanga and Moyo. Hunzvi’s new faction was supported by Chinotimba who now became his deputy with Ndlovu as the secretary general. Allegations of fraud and embezzlement continued to dog Hunzvi’s leadership and by the end of 1999, Hunzvi had been arrested by the police on allegations of corruption and remanded in custody for approximately three months. (He was subsequently released from custody before his case came to trial.) Shortly thereafter, the ZANU-PF politburo re-imposed him as leader of the war veterans with Joseph Msika, ZANU’s vice-president, announcing the fact to a bewildered nation on ZTV toward the end of 1999.

The active involvement of war veterans in the country’s political and economic processes can be traced back to this period of problems within the ranks of the association’s leadership amid serious allegations of corruption and embezzlement of association funds. This was at a time when the War Veterans Board had been disabled and emasculated with President Mugabe’s complicity. This was also at a time of the rise of civic activism in the form of demands for a new people driven and democratic constitution and accountable government. The government was under pressure with its back against the wall first from the war veterans’ demands for payments and civic demonstrations for a new constitution that soon gave birth to a new vibrant labour opposition party. The government enlisted the help of war veterans in brutally suppressing NCA demonstrations in 1998 marking the first partisan political involvement of the former fighters since independence in 1980. This was at a time when the war veterans association had no legitimate leadership and at time when those spearheading the suppression of civic demonstrations were facing serious corruption allegations of defrauding the association’s companies. Most of the former fighters had pooled their funds from the government gratuities to invest in ZEXCOM and never realised the expected returns.

The question to be asked is why the government chose to recognise people who had not been elected to their positions as the leaders of war veterans, people facing serious corruption allegations for prejudicing fellow war veterans? What was the trade off? Why did the ZANU PF government and the state controlled media turn a deaf ear to the legitimately elected executive of the association that had constitutionally and procedurally deposed Hunzvi? Is it any coincidence that these so-called war veterans were spearheading the repression of civil society with impunity and a time that the government had its back against the wall? In my view, it was the unconscionable decision by the government to ignore the elected leadership of the association that deposed Hunzvi and to turn a blind eye to the corruption of the unelected so-called leaders of war veterans that set the stage for the partisan political involvement of war veterans that continues to cast aspersions on their integrity. This development paved the way for the subsequent involvement of war veterans in ZANU PF election campaigns and the violent farm invasions that wrought untold havoc in our economy. An inglorious public perception was created that the former fighters had regressed from being war veterans for themselves to being war veterans for the ZANU PF state.

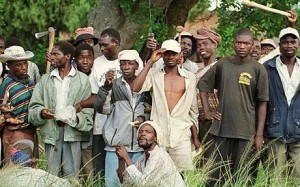

There was a lot of violence and well documented cases of human rights abuses in election campaigns from 2000 onwards that encompassed murder, rape, torture, destruction of property and internal displacement on perceived ZANU PF opponents. All these heinous actions were attributed to war veterans. The defeat of ZANU PF government’s constitutional review proposals in February 2000 saw the involvement of war veterans in violent farm invasions under the banner of the so-called ‘fast track land resettlement programme’. This marked the beginning of the involvement of war veterans in the country’s economic processes. Furthermore, the war veterans became involved in the dubious resolution of labour disputes from around 2002 onwards even before the formation of the Chinotimba led self-styled trade union federation ZFTU.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the pertinent question to be asked is whose agenda were the war veterans pursuing by getting involved in these political and economic processes? Was it a war veterans’ agenda? If so was there any resolution passed by any legitimately constituted forum of war veterans calling them to engage in those activities? This could hardly be the case given that from 1998 onwards Hunzvi and the other characters purporting to be leaders of the war veterans association were not the organisation’s legitimately elected leaders as narrated above.

In the circumstances, I would argue that the ascription and attribution of violent election campaigns and brutal farm invasions to the war veterans association or war veterans in general is totally misplaced. These were the actions of ZANU PF supporters to further their partisan interests and bolster the party’s electoral fortunes by people who happen to be war veterans. It would therefore be a travesty of justice to hold the generality of war veterans or the war veterans association for that matter accountable for the actions of ZANU PF activists doing the party’s bidding. As discussed above, ZANU PF had lost popular support towards the end of the 1990s and could no longer count on the mobilisation of the party’s machinery to campaign for them. It therefore became necessary to enlist the services of some rogue war veterans to prop up their flagging electoral fortunes just as was the case with partisan abuse of the youth militia in ZANU PF election campaigns. It is little wonder that the involvement of the veterans in the country’s political economic processes coincided with the beginning of the breakdown in the rule of law, impunity for crimes committed by ZANU PF supporters and the selective application of justice.

It is noteworthy that war veterans never participated in partisan political party election campaigns under the label of war veterans until the elections of 2000 and thereafter. The major reason for this is that ZANU PF had become so unpopular that it was unable to win free and fair elections in the face of a vibrant opposition presented by the MDC. They had to throw caution to the wind and resort to unorthodox means to retain power at all cost. Hence the need to enlist rogue war veterans, youth militia and the security forces as shock troops to embark on a scorched earth policy ahead of all elections.

In the climate of lawlessness and anarchy it became difficult for war veterans with alternative views to be heard on account of the state’s support for rogue war veterans. My organisation, the Zimbabwe Liberators Platform, formed in response to the wave of lawlessness and anarchy that gripped the country, for example, was subjected to state repression with its assets seized and disposed of by state agents who also claimed to be war veterans. The organisation’s director and programmes coordinator endured a two year long lawsuit for misappropriation of funds that in the end came to nothing. State agents used the time to destroy the organisation leaving no alternative war veterans opposition voice to the ongoing state sponsored mayhem.

The rehabilitation and reorganisation of war veterans is compounded by ZANU PF’s meddling through the imposition of compromised and pliant individuals as leaders of war veterans, some with dubious liberation war credentials. I find it incomprehensible that senior army officers, with impeccable liberation war credentials have to endure the humiliation of subordinating themselves to such leadership on retirement from the defence forces.

All self-respecting and genuine war veterans have their role in the country’s political and economic processes cut out. They have to rise above partisan political interests and become role models in safeguarding the values and ideals of the liberation struggle that encompass freedom, democracy, social justice, respect for human dignity and peace. They should constitute the first line of defence against the violation of these sacrosanct principles of humanity and propagate the respect for the rule of law as the basis of an orderly society. During the war we prided ourselves on the philosophy of self-reliance in the struggle to liberate our country. We believed in liberation through our efforts and not in subcontracting the struggle. We should continue to cultivate a good work ethic and a culture of hard work and not expect to get something for nothing or reap where we did not sow.

We should strive to be successful farmers and entrepreneurs through hard work and not through expropriation, entitlement and preferential handouts ahead of the common people. We should not become negative role models that bring shame on the honour and integrity of the former fighters. Where we feel that our ideas and views are at variance with the people, we should engage in dialogue and persuasion to win their support just like the mobilisation during the war. We should spare a thought for our urban and rural folks who rendered unflinching support to the liberation war and not turn against them in furtherance of retrogressive partisan interests. That way, we reduce ourselves to the notorious level of our former oppressors who indiscriminately committed atrocities against the black population.

We, the former fighters should, through exemplary participation in the country’s political and economic process, help build a new Zimbabwe that future generations will feel proud of. We should uphold a value system founded on respect for the people’s rights, hard work, honour, service and integrity.

Rights reserved: Please credit the author, and Solidarity Peace Trust, as the original source for all material republished on other websites unless otherwise specified. Please provide a link back to http://www.solidaritypeacetrust.org

This article can be cited in other publications as follows: Mhanda, W. (2011) ‘The Role of War Veterans in Zimbabwe’s Political and Economic Processes’, 13 May, Solidarity Peace Trust: http://www.solidaritypeacetrust.org/1063/the-role-of-war-veterans/

References

1. Dzinesa A G. (2000), ‘Swords into ploughshares: Disarmament, demobilisation and re-integration in Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa’, Occasional Paper 120, January, Institute of Security Studies, p.3. < http://www.iss.co.za/pubs/papers/120/Paper120.htm>

2. Mazarire, G. and Rupiya, R. M. (2000), ‘Two Wrongs Do Not Make a Right: A Critical Assessment of Zimbabwe’s Demobilisation and Reintegration Programmes, 1980-2000’. Journal of Peace, Conflict and Military Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, March 2000. University of Zimbabwe, Centre for Defence Studies, p.3.

3. Operation SEED is an acronym for ‘the Operation of Soldiers Employed in Economic Development’ introduced in 1981. It was designed to encourage excombatants to swap their guns for picks and shovels and to work on land acquired by the government for that purpose; ‘Zimbabwe Liberators- Guerillas Today’, Consolidating People’s Power, Afrosoc, Zimbabwe, University of Cape Town: 1981:42

4. Musemwa, M. (1995) ‘The Ambiguities of Democracy: The demobilisation of the Zimbabwean ex-combatants and the ordeal of rehabilitation, 1980-1993,’ Transformation, 26.

5. Dzinesa A G. (2000), ‘Swords into ploughshares’: op.cit., p. 6.

6. Musemwa, M. (1995) ‘The Ambiguities of Democracy’ op.cit. p. 37-8.

7. THE HERALD 18 April 1997

8. Ibid

9. Dzinesa A G., op cit..

10. Chenjerai Hunzvi was a ZAPU political activist who served as the party’s representative in Poland before independence. He subsequently studied medicine there after independence, and did his housemanship at Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals before working at Harare Central Hospital. He subsequently established a private surgery in Harare’s Budiriro high density suburb. Senior ZIPRA commanders have disputed that Hunzvi ever underwent military training

11. Zimbabwe Independent January 16 1998 to January 22 1998

12. Seventy thousand war veteterans were said to have looted the fund of Z$45 million, a great deal of money in 1996. The Daily News, 10 February, 2010.

13. Norma Krieger: From Patriotic Memories to ‘Patriotic History in Zimbabwe, 1990 – 2005; Third World Quarterly, Vol 27, P 1159

14. For instance the remains of freedom fighters like James Bond and Lizwe are still interred at Chikurubi Maximum Prison cemetery and no efforts have been made to locate the remains of Edmund Kaguru (aka Benjamin Mahaka), a former member of the ZIPA MC who was shot and mortally wounded during the Nyodzonya attack and taken back to Rhodesia by Reid Daly’s Selous Scouts.

15. Dzinesa A G. (2000), ‘Swords into ploughshares’: op.cit., p. 6.

16. Meldrum, A., The Guardian, Tuesday 5 June, 2001.

An intresting and well presented account