History and Fiction in the Writing of ‘We Are All Zimbabweans Now’

By James Kilgore – Research Scholar, Center for African Studies, University of Illinois, (Urbana-Champaign).

I began my career as a fiction writer in 2003 at the age of 57. I guess you could say my entry into this world of the writer took place under special circumstances. At the time I was in a California prison, adjusting to a new way of life after spending 27 years as a fugitive. Most of that time I’d spent in southern Africa, working as an educator and helping my partner raise our children. By 2003 all of that was becoming distant memories. To make matters worse, the few bits and pieces of information I did get about events in Zimbabwe were hardly cheering. From afar I was witnessing the descent of a country where I had spent most of the 1980s into political and economic chaos.

After awhile I began to realize what was happening in Zimbabwe was not only a struggle about land and political power, it was a struggle over history. Two competing paradigms were vying for hegemony. Robert Mugabe and his inner circle were advancing what Professor Terence Ranger, would later term “patriotic history.” This vision laid all problems of Zimbabwe past and present at the doorstep of British imperialismwith white Rhodesians occupying a special category of surrogate oppressor. Patriotic history constituted a unifying cry, an attempt to capture public memory and divert the attention of Zimbabweans from any authoritarianism, corruption, and divisions along ethnic or class lines. Patriotic history’s “them and us” clearly delineated the fault lines and papered over any curiosity aroused by the memories of individuals who had suffered at the hands of the Fifth Brigade or those who quietly watched their children starve while political leaders drove by in their BMWs.

On the opposite pole, the seizure of white-owned farms by the Mugabe government prompted a resurrection of colonialist history. The few Western media reports I saw pictured beleaguered white farmers under attack by unrelenting, unreasoning Africans. These accounts typically portrayed whites as innocent victims in this process, a well-intentioned minority who had built up the country during Rhodesia days and subsequently joined hands with black compatriots in reconciliation after independence, only to be reviled and dispossessed. Though I only heard of them peripherally, memoirs by white Zimbabweans/Rhodesians soon burst forth to revive the myths of the past. . (Buckle, 2001 and 2006; Hunter et al. 2001; Harrison 2006) Like its patriotic counterpart, this resurgent white supremacist history involved simplifying and omitting. Blights on the days of white rule such as the migrant labor system, black disenfranchisement, expropriation of African lands conveniently disappeared. Eric Harrison, on a website named after his memoir Jambanja, encapsulated this view neatly in his description of post-1980 Zimbabwe:

Tyranny replaced the democratic process. National self-sufficiency gave way to drastic shortages and malnutrition. Through all this sorry history one thing stood out – the indomitable spirit of the white and black Zimbabweans who were the victims of this insanity. (2010)

As a person in prison and as an historian dual urges struck me. The first was to in some way connect to events in Zimbabwe. On a personal level, this was an effort to transcend my incarceration, to link not only with the place and events, but with the people in this hour of conflict and confusion. Writing would shorten the psychological and historical distance between myself and southern Africa, where the bulk of my family, friends, and personal emotions resided.

Linked to this was the second urge, perhaps more fantastical: to make some kind of meaningful intervention into what was taking place in Zimbabwe. Given my situation, such aspirations seemed almost laughable. The bulk of the political struggles were being fought on the ground, one place I definitely could not be. However, the struggle over history involved, at least to some extent, a war of words. On that battle front, I was in good shape. I had a lot of time to produce words. Certainly I wouldn’t have the last word, but something I wrote might just trigger one or two thoughts in someone far away. For an imprisoned writer, that’s grabbing the gold. Besides, even if my words never reached anyone, the act of writing would help me to put my own thoughts about Zimbabwe in order. I decided to write an historical novel.

Of course I had one big problem in this endeavour-I’d never written a novel before. My one foray into fiction was a short story published in a community magazine in Melbourne, Australia some two decades earlier. Fortunately, to my knowledge, no copies of that feeble effort had survived.

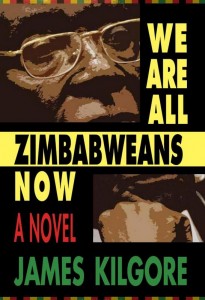

As a novice fiction writer I not only had to create a story, I had to invent a writing process. At the time I started constructing the text, I really had no idea about the details of plot, setting, character, and all the other things they teach people in writing and literature classes. I was flailing in the darkness. When I look back on it, I really don’t see how I ever managed to produce a novel in such ridiculous circumstances, but I did. So let me describe how it happened. I’ll start with a plot summary, then look at how I tied together the historical paradigms that concerned me with the story I wanted to tell. After that I’ll outline how I actually developed the ability to write what became We Are All Zimbabweans Now.

Plot Summary

The story takes place in early 1980s Zimbabwe, right after independence. The protagonist Ben Dabney, a young American post-graduate student in History, travels to Zimbabwe with a totally idealized picture of Robert Mugabe and the Zimbabwean notion of reconciliation. Ben sees Mugabe as the embodiment of the spirit of Gandhi, Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King, a logical candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize. As an historian, Ben aims to tell the story of the Zimbabwean miracle of reconciliation to the world.

Obviously this is going to be story of disillusionment. Ben wends his way through a romance with an ex-freedom fighter, a conflict with the Fifth Brigade in Matabeleland and harassment from the C.I.O. when he tries to investigate the death of Elias Tichasara, a ZANLA guerrilla leader who died in an unexplained car accident right before independence. In the end Ben abandons his project of writing praise poetry for Mugabe and re-works his approach toward history and ultimately life itself. That’s it in a nutshell.

Now let me explain how I put it together.

Developing An Approach to the History

My first priority was linking my approach to history with the story. Many writers of historical fiction ignore notions of approach or paradigm, often seeing a hard divide between history and historical fiction. Author William Martin, for example, argues that:

The historian serves the truth of his subject. The novelist serves the truth of his tale. (2010)

Guy Vanderhaeghe concurs:

To what do I owe my primary allegiance? The demands of history or the demands of the novel? In the end, I clearly opted for what I felt was necessary to ensure the artistic integrity of the novel. I entered the camp of Mark Twain who said, ‘First get your facts. Then do with them what you will.’ I decided the noun novel was more important than the adjective historical. (2005)

For many such writers, the goal is to achieve what is alternatively referred to as authenticity, believability, or verisimilitude. The key to all this rests primarily in the details of setting. While lawyers, politicians and business leaders often proclaim that the devil is in the details, Vanderhaeghe offers a totally different slant:

As a writer of fiction I live and breathe minutiae, quirky odds and ends of information. For a novelist, it is not the devil that is found in the details. The details are where God resides. A novel cries out for texture to lend it verisimilitude. (2005)

In this same paper, Vanderhaeghe goes on to argue that writing historical fiction somehow liberates a writer from the shackles of academic rigor. As he put it: “the lack of evidence provided me with freedom.”

Hence, the reflections of writers of historical fiction often dwell on quests for the obscure, the hunt for memoirs which detail the color and textures of the curtains in the living room or describe how to make a jug of mead. While I spent considerable time doing such research myself, (which I will discuss below), the authenticity of my story didn’t revolve around such details. Rather, the believability of this tale would ultimately hinge on my ability to recreate the political and historical landscape of Zimbabwe in the 1980s. First of all this required me deciding what I actually made of that history, where I stood on the debates and interpretations of Zimbabwean history in the 1980s and how that linked to my project of writing a novel in the early 2000s.

Doing this from thousands of miles away in the absence of access to the Internet or a library, meant relying on a few books sent in and tapping into my own knowledge and experience in an effective way. I began by reconstructing the evolution in my own thinking about Zimbabwean history. I harkened back to 1983 when I was teaching Form 2 History at Harare’s Mabvuku High School. The Ministry of Education had just scrapped the Rhodesian syllabus and inserted a new nationalist curriculum in its place. The problem was, at that time there were no textbooks or support materials available. We had to create our own. To teach the first Chimurenga/Umvukela, I secured a copy of Terence Ranger’s Revolt in Southern Rhodesia. I spent many hours pouring over the ins and outs of Kaguvi, Nehanda, and Mukwati, preparing detailed notes for my students which I then transferred to printed sheets via the mimeograph machine in the hallway outside the Headmaster’s office.

This was the starting point of my engagement with nationalist historiography-the idea that the colonized were not mere passive victims in the process of colonialism but rightfully resisted. What a great leap forward this was from the leftover Rhodesian textbooks, The Patterns of History, which propagated notions like blacks being better suited for slavery because dark skins could endure the hot sun.

The nationalist historiography helped to unearth pockets of African resistance in all corners of colonial society and demonstrated how the struggle for independence was a long, slow, uneven but inevitable process. The insights of nationalism, combined with my reading of Marxist political economy, guided me through my teaching and writing in the 1980s. This culminated in contributing a number of chapters to what became the most popular O level textbook in the country, People Making History (1991 and 1994), a book that, perhaps regrettably, is still sold today.

Fortunately, my own evolution did not stop there. For while the nationalist historiography and Marxist political economy shed light on significant aspects of colonial and post-independence history, they also cast some rather malevolent shadows. In particular, the infatuation with the success and moral authority of the armed struggle made many of us too quick to rise to the defense of Mugabe and his inner circle. Most tragically, the light of nationalist inspiration blinded me and a large swath of people in Zimbabwe at the time (including historians) to the scale and significance of the military offensives by the Zimbabwean government forces in Matabeleland during the 1980s. We heard reports of slaughter and repression from people who lived in Matabeleland. We believed those tales but from our intellectual comfort zone the violence in Matabeleland remained a minor blemish on a glorious movement, something akin to the Nhari rebellion or the assassination of Herbert Chitepo. We were also certain (hopeful in fact) that the bulk of “dissident” activity was instigated by the apartheid regime. We still wanted to deny that ethnicity or regionalism could play a significant role in an obviously successful nationalist project. It took a long time to shake the foundations of that belief.

Ultimately my discontent with this nationalist paradigm went beyond giving Gukurahundi and all its ramifications a rightful place in history. There were class and gender issues which nationalist historiography also skimmed over. Nationalist-oriented historians focused on the political realm at the highest levels-party structures and position papers, rivalries and intrigues within organizations, and post-independence twists and turns in policy and personnel. My experience with domestic workers, both as a teacher in an evening school as well as in my research, brought my lens down to a lower level. I adopted a “history from below” perspective, one which I saw at that time as a deepening of, rather than a rejection of the nationalist approach. While I remained within the nationalist paradigm, looking at post-independence Zimbabwe from below prompted me to ask some bigger questions, particularly which classes benefited from the ZANU-led government and why.

Furthermore, nationalist historiography and histories of nationalism generally had a woeful record when it came to gender issues. Much of nationalist practice and history kept women in the background. Party political positions defended womens’ equality but actions reflected something very different. My research into domestic workers led me to engage with another aspect of history from below, the gendered nature of Zimbabwean society and the experience of working class and rural women.

In addition to the above issues further consideration of nationalist historiography brought out critiques with regard to issues of ethnicity, spirituality/ religion, urban-rural divides, the implications of political violence as a strategy for liberation and the nature of democracy. Somehow I needed to draw all these threads together and weave them into a story.

I was determined that a reader of my work would neither conclude that Robert Mugabe was a saintly savior of the African people nor that whites in pre- and post-1980 Zimbabwe were uniformly champions of peace and racial equality. But I had to complicate things much further while reminding myself that there were aspects of the nationalist historiography such as the emphasis on political economy and race which I could not cast completely aside.

In the midst of juggling the complexities of all this, a further complicator arrived one day at mail call, Luise White’s book The Assassination of Herbert Chitepo (2003). Her work tore apart notions of absolute historical truth in Zimbabwe, freeing me from the idea that all history must be knowable, that circumstances could never overwhelm the intrepid researcher in a quest for truth. White reminded me that history was not a murder mystery to be solved but rather a set of questions to pursue, guided by a curiosity and at times a desire to be surprised by what you find rather than to simply uncover more evidence which already substantiates what you “know.”

This morass of ideas continually raced through my head as I lay on various prison bunks or stood in line for trays of goulash in penitentiaries in places like Lompoc, Tracy and Susanville. But without the time for reflection with which prison authorities were kind enough to provide me, I would never have been able to complicate Zimbabwean history enough to write a novel with any measure of authenticity. In my mind, no historical fiction could carry much weight if the writer wasn’t as concerned with the interpretations and debates of the history, indeed the politics of the history, as in the vitality of the story. My allegiance was as much to history as to the novel. History in this instance was not only the facts, but how historical theories, interpretations, and debates enter the political arena.

Truth v. Fiction: What to Fictionalize

The second issue I had to address was the question of fictionalizing versus telling the whole truth. The spectrum of historical fiction ranges from acute realism to magical realism to alternate history to historical fantasy- from tracing every little fact and detail in precision to making it all up.

As an academic historian of sorts and a history teacher, it’s not surprising that I fell on the realist end of the spectrum, especially since I chose to write about events that took place in Zimbabwe at a time I lived there. Making use of my own experiences seemed to be a vital contribution to the authenticity of my work.

However, since this exercise would inevitably rely heavily on my memory of events rather than historians’ accounts, I decided to fictionalize all the characters who actually appear in the story with the exception of Robert Mugabe. “Bob” just had to be there.

This wasn’t simply a creative choice. In the absence of access to sources, I wasn’t confident I could gather the necessary details of the lives of people like Eddson Zvobgo, Enos Nkala or Joyce Mujuru to avoid major errors of fact.

Of course there were some grey areas in terms of fictionalization. A number of the characters in We Are All Zimbabweans Now bear quite close resemblance to real people. The most obvious example would be Elias Tichasara, a liberation fighter whose untimely death in a car accident looks a lot like Josiah Tongogara’s. I chose to fictionalize him simply because his totally fictionalized son and former lover were central characters in my plot. From where I was I had no idea if there was a Josiah Tongogara, Jr. or even an ex-partner of Tongogara’s who had his child. Rather than run the risk of slandering such people if they existed, I chose to fictionalize the character, perhaps at the loss of some authenticity.

Many other characters are amalgamations. For instance, the somewhat Zvobgoesque Pius Manyeche ultimately had a Maurice Nyagumbo ending. And some of Ben’s confrontations with local culture, like kneeling down to a Shona-speaking woman, are incidents which actually occurred to people that I knew in Zimbabwe in this period. At times, my line between fiction and true history was quite fine.

However, relying on so many fictitious characters meant paying attention to the accuracy of other elements of the novel. Other than trying to ensure a factual accuracy about events of the period, I also spent considerable time trying to re-create the sensory context so important for a work of fiction. My God wasn’t in the details but I couldn’t neglect those details either. I didn’t want to fictionalize sadza into pasta or Tanganda Tea into Twinings. I spent hours making up what writers call a “sensory diary”, a listing of things I saw, heard, smelled, tasted or touched during my time in Zimbabwe. This list was greatly enhanced by the opportunity to read novels by Shimmer Chinodya (1989) and Tsitsi Dangarembga (1988), as well as the brilliant collection of interviews, Mothers of the Revolution by Irene Staunton (1991).

This prompted some serious self-reflection. How much had my own perception and analysis of events altered my own memory of them over the years? Could I trust myself as a source? How could I verify my own memories given the limitations of my status of incarceration?

For example, I was convinced that I could still accurately recall the coating that roasted matumbu left on the roof of my mouth and that a sip of cold Castle would wash it away. I was also fairly sure that rural bus conductors used to walk around on the top of moving buses but I couldn’t exactly recall an incident of this taking place. From a California prison cell, I couldn’t test such hypotheses. I chose to accept them as authentic, though I could not verify their absolute “truth.”

Historical Debate as Plot Device

In the first draft of We Are All Zimbabweans Now, Ben Dabney wasn’t an historian. Then I read The DaVinci Code. While many criticisms can be made of Dan Brown’s work, The DaVinci Code very effectively demonstrated the connections between the power to write and propagate history and the actual wielding of political power. Ultimately the journey of Brown’s protagonist was a quest to unpack the forces that lurked behind popular perceptions of the church and religious history. I believed Zimbabwean history held at least as many controversies and intrigues as the history of the church, so I sought to write a novel that would unpack a few of them. Hopefully, though, I didn’t make up quite as many events and historical forces as Dan Brown did.

Historical debate enters the plot thread of We Are All Zimbabweans Now via Ben. He is an historian who begins with a project of writing the story of his hero, Robert Mugabe. At this point Ben sits squarely in the “great man” school of history, albeit with a nationalist slant. However, shortly into his research, Ben’s very supportive supervisor leaves and a Professor Latham takes over. Latham is a Briton who longs for the glory days of the empire. Latham threatens to pull the plug on Ben’s funding unless he interviews more whites from the previous government. The sets off the debate inside the historian part of Ben’s mind.

Then the ZANU ruling circles try to woo Ben. Cabinet ministers welcome his project, promise him the red carpet treatment including an interview with Mugabe if he follows their recommended path. They are lining him up to write what likely would have been the “patriotic” history of that time.

Next Ben meets a young British woman historian at the archives. They enter a short, stormy affair where Ben momentarily becomes a part of a cynical expatriate circle, those who are revolted by the racist attitudes of local whites but denigrate any expectation that a Mugabe-led government can do much better. They push Ben toward yet a third historian’s role, that of distant, comfortable expatriate eating roast beef dinners served by domestic workers, bemoaning the lack of a good red wine in the shops, and writing obscure, self-serving tomes about minutiae.

Finally, through various sets of circumstances, Ben moves out of these circles and travels to the high density areas, then to rural Zimbabwe. His discussions with Marxist guerrilla-turned-agricultural co-op chairperson, Wonder Chitiyo, alert Ben to a hidden history, the story of what took place in the past and what continues to go on in the fields and working class urban areas of Zimbabwe, the places where the majority of the population lives.

Ben’s journey as an historian unfolds as he tries to sort out which path to follow. In the course of his explorations, he stumbles into the violence in Matabeleland and another side of hidden history emerges. When he tries to bring the violence into the public light, he runs up against the authorities.

Throughout the book I have attempted to portray this historical debate not only through Ben’s experience but in his internal monolog as well. Unlike Dan Brown’s characters, Ben is an historian. He can use the terminology of history to frame the discourse of the monkeys that chatter away in his head.

These contestations over history surface in the title of the book as well. Ben first hears the phrase “we are all Zimbabweans now” from an elderly working class gentleman in a café where Ben is the only white person. As Ben takes his food from the counter and looks for a place to sit, the old man slides out a chair at his table and offers it to Ben, saying, “take a seat, we are all Zimbabweans Now.” In this instance, the phrase is inclusive, reflecting a new attitude where blacks and whites can sit together at the same table in a way they weren’t able to do before independence..

By the end of the book, Robert Mugabe has appropriated the phrase and it embodies a new politics. When he says “we are all Zimbabweans now”, he means that everyone must come under the hegemony of one party – ZANU. To be Zimbabwean is to be ZANU. To be outside the party or critical of the party is to be something other than Zimbabwean. Expropriating the expressions of ordinary people and using them to express the political project of a ruling party is part of the process of re-writing history- akin to dubbing the farm seizures the Third Chimurenga or labeling MDC members dissidents. The power to write history, is also the power to create the discourse which is used to convey that history.

Putting It All Together

Weaving all of these processes into a work of fiction was a lengthy learning process. Not only did I have to worry about notions of history but I had to build my own capacity to inject all of this into a novel. In the absence of mentors or literature classes, I relied primarily on getting invaluable feedback on various drafts from friends and reading a lot of how-to books about fiction writing- how to develop a plot, how to build characters, how to write dialogue, etc.

Ultimately my novel went through probably half a dozen drafts. I completed the first attempt on a forty year old manual typewriter with a fading ribbon. Then I moved to another prison and struck it rich gaining access to a computer with a hard drive and a printer. I was able to print out my work and read it back to myself in my cell late at night while everyone else slept. By the time I was ready to produce the final product, I had moved again and lost all access to technology. I had to rely on pen and paper to write out 570 pages of semi-legible scribbles which a number of my dear friends and family typed onto a computer and sent to the publisher. Imagine my joy a few weeks later when my wife told me during a phone call that We Are All Zimbabweans Now had been accepted by Umuzi Publishers in Cape Town.

Though my writing process was quite atypical, I wonder whether my research process was truly impoverished. Certainly at a technological level, I took a step back in history to the pre-Internet era. Also, my isolation from other scholars or even people with a rudimentary knowledge of Zimbabwe was clearly a handicap. Yet, in some ways, incarceration provided opportunities to reflect and analyze that few scholars and writers in the twenty first century experience. I had no meetings to attend , no deadlines to meet, no children to pick up, no email to check, no SMS messages waiting. I’d never even seen an iPod or a smart phone. I was “free” from such chains. I’m not sure that I’m richer for this experience or that I will lock myself away in a room to engage in reflection for further works, but I’m also more certain than ever that there are many roads to the production of knowledge and the writing of novels and all of them are not paved with URLs and RSS feeds.

Rights reserved: Please credit the author, and Solidarity Peace Trust, as the original source for all material republished on other websites unless otherwise specified. Please provide a link back to http://www.solidaritypeacetrust.org

This article can be cited in other publications as follows: Kilgore, J. (2012) ‘History and Fiction in the Writing of “We Are All Zimbabweans Now”‘, 4 May, Solidarity Peace Trust: http://www.solidaritypeacetrust.org/1175/the-writing-of-we-are-all-zimbabweans-now/

References

Barnes, T. et al. 1991. People Making History, Book 3.Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House.

________. 1993. People Making History, Book 4.Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House.

Brown, Dan. 2003. The DaVinci Code, New York: Double Day.

Buckle, C. 2001. African Tears: The Zimbabwe Land Invasions. London: Covos Day.

________. 2006. Beyond Tears: Zimbabwe’s Tragedy. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball.

Chinodya, Shimmer. 1989. Harvest of Thorns. Harare: Baobob.

Dangarembga, Tsitsi, Nervous Conditions, (London :Womens’ Press, 1988)

Harrison, Eric, http://www.jambanja.net , retrieved 1 Feb, 2010;

Hunter, G et al. 2001. Voices of Zimbabwe: The Pain, The Courage, The Hope. London: Cavos Day.

Martin, William. A Few Thoughts on Historical Fiction, (Accessed at: http://web.utk.edu/~wrobinso/590_lec_hisfic.html, October 3, 2010)

Ranger, T. O. 1967, Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-7: A Study in African Resistance. London: Heinneman.

Staunton, Irene. 1991. Mothers of the Revolution: The War Experiences of Thirty Zimbabwean Women, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Vanderleaghe, Guy, 2005.“Writing History vs. Writing the Historical Novel’, A Talk Presented to the Montana Historical Society, October 2. Helena, Montana. U.S.A

This is fascinating as I am writing weekly column for the Zimbabwe herald and I come across my shamwari, good friend, John’s book chapter. Please John get in touch! We travelled on the village bus once in Zimbabwe before all the changes. I need a copy of the book. The email address is above or google me under Zimbabwe herald.

Hi John

I’d love to get a copy of the book and review it for The Australian. You may recall we met with Sekai back in the early 90s. If only I had known the story sitting in my living room. Hopefully I can still tell it today. Adamshand@hotmail.com

Cheers

Adam