The Changing Politics of Matebeleland since 1980

by Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni – Associate Professor of Development Studies at the University of South Africa

Introduction

I think the best way to understand the present day manifestations and character of Matebeleland politics is to situate them properly historically and politically within the broader terrain of the development of the idea of Zimbabwe and the eventual configuration of the Zimbabwe nation-state. The changing nature of politics in Matabeleland is largely a response to realities and perceptions of exclusion, marginalisation and confinement to second class citizenship of Ndebele-speaking people that began in 1980. The politics that is emerging from Matebeleland region is that of protest to perceptions and realities of exclusion, marginalisation and domination. The launch of such radical formations as the Matebeleland Liberation Front (MLF) last year calling for complete secession of Matebeleland and Midlands regions from Zimbabwe is the climax of regional politics of frustration and resentment of domination.

President Robert Mugabe’s recent response to the developments taking place in the MDC led by Welshman Ncube and his seemingly overt support for Arthur Mutambara to remain as Deputy Prime Minister and refusal to swear-in Welshman Ncube as the new Deputy Prime Minister is fuelling perceptions of Ndebele-speaking leaders being unwanted and excluded from the corridors of power. It is therefore important to deploy a sober analysis that seeks to understand the motive forces behind the character of politics in Matabeleland since the 1980s. While one can get some glimpse of the core grievances from such forums as newzimbabwe.com and many others, it is equally important to situate the Matebeleland problems historically.

The idea of Zimbabwe and Matabeleland question

The idea of Zimbabwe is traceable to the 1960s. It emerged as a nationalist idea and an imagination of the postcolonial nation-state. The idea emerged within a terrain saturated with various ethno-cultural societies such as the Matebele Home Society, Monomotapa Offspring Society, Kalanga Cultural Society and many others-socio-cultural societies that indicated where the people were coming from and how they were responding to colonial environment and how they defined themselves identity-wise.[1] The naming of associations indicated a formative consciousness that was torn-apart between pre-colonial nostalgia and colonial realities. Zimbabwean nationalism had to spring from this milieu.

The name of the imagined nation had to be indigenous. The Great Zimbabwe heritage site that is closely associated with the Karanga people (a branch of Shona as an enlarged identity) provided the name. Michael Mawema, a Karanga is credited for coming up with the name during his short stint as the interim president of the National Democratic Party (NDP). But the first political formation to officially use the name Zimbabwe was the Zimbabwe National Party (ZNP) an insignificant party that was formed by some Karanga-speaking politicians that had broken up from NDP. From this outset, a voice from Matabeleland coming through some members of Matebele Home Society protested against the choice of the name Zimbabwe for the imagined nation. They reasoned that it was an ethnic name that was not accommodative of other peoples. They preferred the name Matopos as inclusive and non-ethnic.[2] Ethnicity was beginning to be a factor in the imagination of the postcolonial nation-state itself.

African nationalism as the medium of implementation of the idea of Zimbabwe became deeply interpellated by ethnicity from its birth despite some pretensions of unity by the early nationalists. At the centre of articulation of nationalism were such considerations as what the foundation myth of the imagined nation-state was, and which heroes, symbols and history had to be projected as an anchorage of the imagined nation. Beginning with the naming, Shona histories, symbols and heroes were increasingly elevated into anchorages of the imagined nation. This has partly to do with the fact that a majority of postcolonial nation-states had to be built and crystallise around the dominant ethnie. But nationalists had the mammoth task of creatively managing and balancing such vectors of identity as race, class, ethnicity, region, gender, and generation as they imagined a unitary postcolonial nation-state. The difficult question is: Were there real nationalists existing as de-tribalised actors committed to the imagining and building a stable nation? Was the label nationalist not only a respected one that masked tribalism? Did we not have lip-service nationalists who only assumed nationalist identities in front of crowds and then withdrew to their primal tribal identity soon after? These are important questions that beg for responses.

The 1963 split in the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) that gave birth to a Shona dominated Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) remains one important event that indicated how tribalism and ethnicity were deeply embedded within nationalism. However hard those who were involved in this split deny the prominence of tribalism and ethnicity as a factor behind the split the subsequent events spoke loudly about the role of ethnicity in spoiling the birth of a nation. The immediate post-split ZAPU-ZANU faction fights in Harare, Gweru, Bulawayo and other sites took clear tribal and ethnic dimensions. Later splits including the one that resulted in the formation of the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (Frolizi) and others also indicated how ethnicity was playing havoc within nationalist politics. The same is true of postcolonial split that rocked the MDC in 2005. Even factions within ZANU-PF indicate the reverberation of regional, kinship, clannish, ethnic and tribal alignments.[3] In short, the liberation struggle became a terrain of re-tribalisation of nationalism with particular ethnic groups positioning themselves to lead and dominate the imagined postcolonial nation. Even a seemingly unitary Shona identity unravelled as the Karanga fought to eliminate the Manyika and the Zezuru fought for ascendance over the Karanga. Along the way lives were lost due to what Masipula Sithole termed ‘struggles within the struggle.'[4]

The sum of all is that the Zimbabwe nation-state that was born in 1980 was a product of a deeply tribalised nationalism. The nationalists who spearheaded the liberation struggle dreamt in both nationalist and tribal languages and terms. The nation-state was therefore born with a terrible ethnic-tribal birth-mark. As put by Eldred Masunungure, Zimbabwe as a state came into being in 1980 but Zimbabwe as a nation did not.[5] There was outright and unapologetic building of the state as a ‘Zanufied’ and ‘Shonalized’ political formation where other political actors like PF-ZAPU that drew most of its support from Matabeleland and Midlands regions had no dignified space and Ndebele-speaking people were an inconvenience that had to be dealt with. This mentality was clear from music, symbols, heroes and national celebrations of independence.

Zimbabwe and the Matebeleland question

As noted above Zimbabwe was born out of an armed liberation war spearheaded by ethnically fragmented leadership, fought by equally ethnically fragmented freedom fighters and supported by masses that were socialised into tribal politics. It was against this background that ZANU-PF electoral victory in 1980 was celebrated as not only a victory of a liberation movement over settler colonialism but also as victory of Shona political elite over Ndebele political elites in PF-ZAPU.[6] While ZANU-PF built their political legitimacy on their nationalist liberation war credentials, they also openly connected the party, the state, and the nation to Shona historical symbols.

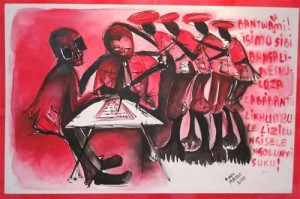

This set the stage for an ethnic showdown between the triumphant Shona and the defeated Ndebele that became openly violent in 1982. On this issue, Norma Kriger noted that from the very day of achievement of independence, the triumphant Shona-dominated ZANU-PF leadership displayed a unique desire to build a ‘party-nation’ and a ‘party-state’ that excluded other political formations, crafted around and backed by ZANU-PF’s war-time military wing (ZANLA) and Shona historical experiences. Specific party slogans, party symbols, party songs, and party regalia of the liberation war time continued to be used at national ceremonies like Independence and Heroes Days.[7] It was amidst this fanfare and celebratory mood that Shona triumphalism unfolded against Ndebele particularism reeling under a feeling of defeat.

Through music and dance, the triumphalism of ZANU-PF over PF-ZAPU was openly displayed and conveyed to everybody as though the liberation struggle was a duality between the Shona dominated ZANU-PF and the Ndebele dominated PF-ZAPU. A decidedly partial history of the liberation war and a decidedly partial imagination of the state and the nation ensued backed by an openly biased historical master-narrative of the struggle for independence. The typical example of that history was David Martin and Phyllis Johnson’s The Struggle for Zimbabwe: Chimurenga War freely distributed throughout the country into every school and college.[8] This book became the official history of ZANU-PF and ZANLA, celebrating their centrality in the struggle while at the same time sidelining the contribution of PF-ZAPU and ZIPRA.

The triumphant ZANU-PF politicians immediately used the state controlled media to cast PF-ZAPU, its leader Joshua Nkomo, and its military wing (ZIPRA), as no heroic liberators, as no committed nation-builders, but as a threat to the country’s hard won independence.[9] Historians like T. Ranger, N. Bhebe, and E. Sibanda have tried to add the Matabeleland narratives into the story of nationalism through Matabeleland focused research in recent years.[10] This academic compensation has not been accompanied by a clear drive for political and economic inclusion of Ndebele people into the mainstream of post-colonial Zimbabwe save for the Unity Accord of 22 December 1987. Up to now Shona history, Shona symbols, and rituals still underpin state ideology at the exclusion of the Ndebele. Even such minor issues such as which news bulletin comes first on ZTV is permeated and driven by imperatives of Shona-Ndebele power imbalances. News in the Shona language must always come first. But in democratic countries like South Africa where there are eleven recognised official languages there is no rigid format of which news in which language comes first.

The central state of Zimbabwe sanctioned deployment of military and ethnicised violence against the Ndebele in the period between 1982 and 1987 within this background. What happened deserves some close analysis because it reveals the behaviour of the central state and how it handled what was considered a form of dissidence of the Ndebele speaking people. The key feature of this period was the attempt by ZANU-PF to crush PF-ZAPU that had constituted itself as the strongest opposition in the country. PF-ZAPU and Joshua Nkomo were ‘provincialised’ and stripped of their nationalist liberation credentials to the extent that Nkomo was openly disparaged as the king of the Ndebele and a father of dissidents.[11]

The open exclusionary state practices took the form of preferential treatment of ex-ZANLA as a victorious force, use of exclusionary language by the political leadership of Zimbabwe, and exclusion of Ndebele history and symbols from the imagination of the new nation. These issues combined to create what eventually became known as the dissident situation in Matabeleland. ZANU-PF desperately needed such a situation to justify its crackdown on PF-ZAPU and its military wing using state power.

Violent handling of ‘dissidents’: Gukurahundi and the Ndebele

Eliakim Sibanda has noted that ‘The crisis in Matabeleland started in the army.'[12] This means that any analysis of how the Shona dominated central state dealt with the Ndebele-speaking people as dissidents must take into account the complexities of a tale not only of politicised ethnicity and abuse of state power, but also a story of problematic integration of ex-ZANLA, ex-ZIPRA and ex-Rhodesian forces into the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA). It is also a tale of problematic nation-building that was exclusivist as well as part of elite politics of competition for power and nationalist vendettas. As early as November 1980, the integration of forces was hit by its first crisis when ZIPRA and ZANLA forces fought against each other in Assembly Points (APs). This ZIPRA-ZANLA fights spread to eNtumbane, Ntabazinduna, Connemara, Chitungwidza, and Silalabuhwa.[13]

The underlying cause of all these violent clashes had to do with a combination of inflammatory political speeches by ZANU-PF leaders, open discrimination of ZIPRA, open favouritism of ZANLA, and abuse of PF-ZAPU leaders to whom ZIPRA was loyal. Kriger noted that ZANU-PF began to behave as though Zimbabwe was a one party state-‘In other areas, too, ZANU (PF)’s grass-roots supporters and its national leadership exhibited a one-party mentality.'[14] The ZANU-PF slogans were openly provocative and disparaging of PF-ZAPU, the person of Joshua Nkomo and the liberation credentials of ZIPRA. This led Josiah Chinamano, a deputy president of PF-ZAPU to warn that these slogans would incite the anger of armed ZIPRA forces without any political platform from which to answer back except through their guns.[15]

Indeed the continued exclusion of ZIPRA, PF-ZAPU, and the entire leadership of this party from the imagination of the new nation, the attempt to belittle their contribution to the liberation war and the monopolisation of the media by ZANU-PF made the people of Matabeleland and ZIPRA agitated, restless and unsure of their security in Zimbabwe. On the other hand, ZANU-PF was bent on eliminating PF-ZAPU and its leadership as they considered it an obstacle to the agenda and drive for the one-party state in Zimbabwe. This agenda was loaded into numerous speeches by ZANU-PF leaders that included Enos Nkala who openly stated that PF-ZAPU and ZIPRA were not heroes-‘They contributed in their own small way and we have given them a share proportional to their contributions.'[16] Following the first clashes between ZIPRA and ZANLA, Edgar Tekere, another ZANU-PF leader openly sided with ZANLA and blamed ZIPRA. He stated that ‘We did not need his army in the war, so why are they making a nuisance of themselves now?'[17] To him, ZIPRA and Rhodesian forces were not to be integrated into the new national army-‘the government must work seriously and quickly for the abolition of ZIPRA and Rhodesian armed forces.'[18]

A feeling of being unwanted developed not only among ZIPRA forces but also among the people of Matabeleland both loyal to Joshua Nkomo and PF-ZAPU. As the ZIPRA found themselves being accused of disloyalty, some began to desert from ZNA with their arms back to the liberation-wartime bush operational areas. Some were escaping torture and witch-hunts that were masterminded by ZANU-PF and ZANLA. ZIPRA found themselves in a very unenviable position within the ZNA. One ex-ZIPRA colonel had this to say:

Say you’re a platoon commander. You find you can’t take decisions. Someone beneath you becomes the kind of proxy commander. I was a colonel, mostly in charge of training at Llewellyn. Two officers committed a crime. They got into a hospital ward and wanted to rape female patients. These guys were reported to me as the senior commander. I remanded them for court martial. But because I was the senior person ordering a court martial-I a ZIPRA-those men were immediately promoted to majors and the whole case ended there. We were there as senior officers but we had no power. All the powers were given to ZANLAs. A ZANLA is more powerful than a colonel.[19]

The violent clashes between the ZIPRA and ZANLA, the desertion of some ex-ZIPRA from the national army, the exploitation of the antagonistic situation by apartheid South Africa via Super ZAPU and the ‘discovery’ of arms caches in PF-ZAPU owned farms around Bulawayo gave government the pretext to use state power to crush PF-ZAPU.[20] ZANU-PF wanted to gain control in the south-western part of the country and to consolidate its power. As noted by Brian Eric Abrams, ZANU-PF and the state ‘developed a clear message, sharp media campaign and a multi-layered military response to achieve its highly focused political goals.'[21] Within this ZANU-PF political agenda, PF-ZAPU was a party that sponsored dissidents, Joshua Nkomo was the father of dissidents, every young Ndebele man was a potential dissident, all ex-ZIPRA including those serving in the army were dissidents, and the entire population of Matabeleland constituted a dissident community.[22] State sanctioned, military-style and ethnicised violence was unleashed on all Ndebele-speaking people between 1982 and 1987. The storm-troopers in this violence were a combination of a select, Shona-speaking Fifth Brigade, specially trained by Koreans in cruelty and torture of its victims, ZANU-PF Youth Brigade, ZANU-PF Women’s League and other regular forces.[23] The time of violence is remembered as Gukurahundi atrocities. The military Brigade that carried out the atrocities is remembered as Gukurahundi. Gukurahundi is a Shona name for early rains that wash away chaff of the previous season. The chaff to be washed away was this time the Ndebele-speaking people.

The Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP) and the Legal Resources Foundation (LRF)’s Report, Breaking the Silence: Building True Peace: A Report on the Disturbances in Matabeleland and the Midlands, 1980-1989, provides crucial details of how a military operation orchestrated through Fifth Brigade (Gukurahundi) became a bizarre combination of random killing of every Ndebele-speaker, hunting and killing of every PF-ZAPU supporter, raping of Ndebele women and girls, as well as abduction, torture, and forcing every Ndebele-speaker to switch to Shona language and then support ZANU-PF.[24] What started as a mission to stamp out dissidents became from start to finish an ethnicized crusade to make the Ndebele account for the nineteenth century raids on the Shona, and a purely anti-Ndebele campaign that deliberately conflated Joshua Nkomo, PF-ZAPU, ex-ZIPRA and every Ndebele-speaking person into a dissident, dissident collaborator, dissident sympathiser and sponsor.[25] This was a situation where the state itself became tribalist with ethnicity being openly used as an instrument to eliminate a rival ethnic group.

The Fifth Brigade-a military unit outfit answerable to the then Prime Minister Mugabe that was said to be politically compliant to ZANU-PF political philosophy was only withdrawn from Matabeleland and the Midlands in 1987 following the signing of the Unity Accord. Before the Accord, the Fifth Brigade committed serious atrocities characterised by brutal and indiscriminate state sanctioned violence targeting Ndebele speaking communities. The carnage started in 1982 and ended in 1987 claiming the lives of over 20 000 civilians.[26]

The impact and meaning of Gukurahundi in Matebeleland

More than any other violent episode in post-colonial Zimbabwe, the Gukurahundi episode reconstructed and reinforced Ndebele identity resulting in deep polarisation of the Zimbabwe nation. Bjorn Lindgren noted that the atrocities carried out by the Fifth Brigade, heightened the victims’ awareness of being Ndebele at the cost of being Zimbabwean.[27]

While this violence was meant to destroy Ndebele particularism as a threat to Shona triumphalism, its consequences were the reverse. The openly ethnic nature of the violence pushed the Ndebele into an even greater awareness of their differences with the Shona. Lingren, wrote that ‘people in Matabeleland responded by accusing Mugabe, the government and the ‘Shona’ in general of killing the Ndebele.'[28] Besides the Fifth Brigade atrocities instilling fear in Matabeleland and the Midlands, it heightened the victims’ awareness of being Ndebele and a sense of not being part of Zimbabwe.[29]

The Unity Accord signed between PF-ZAPU and ZANU-PF on 22 December 1987 amounted to nothing less than a surrender document where the PF-ZAPU politicians threw in the towel and allowed PF-ZAPU to be swallowed by ZANU-PF. The only positive result was that atrocities stopped. Beyond that, the Accord became just a form of nationalist leaders accommodating each other across ethnic division but leaving the people still divided. It was very far from being a comprehensive conflict resolution mechanism.[30] Bitterness and the memory of having lost family members, relatives and friends remained engulfing those areas where the Fifth Brigade and the dissidents operated. This was confirmed by oral interviews that I carried out in 2002 in Bulawayo and Gweru relating to how the Ndebele perceived the military in Zimbabwe. Every interviewee remembered the military in the context of how the Fifth Brigade killed innocent people.[31]

Ndebele particularism emerged out of this violence highly politicised and wounded posing a danger to the pretences of a unitary nation-state of Zimbabwe. In the first place, radical Ndebele counter-hegemonic ethno-nationalism manifested itself in the form of radical Ndebele cultural nationalism and secondly in the form of radical Ndebele-oriented pressure groups that openly questioned the dominance of the Shona in employment in general, senior civil service, security and education as well as open neglect of economic development of Matebeleland and the Midlands regions. Some radical Ndebele-speaking people began to question the value and benefit of associating themselves with the whole idea of a unitary Zimbabwe state that was openly used to oppress and kill them. This spirit manifested itself more openly in the formation of such radical Ndebele pressure groups as Vukani Mahlabezulu, Imbovane Yamahlabezulu, ZAPU 2000 as well as Mthwakazi Action Group on Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in Matabeleland and Midlands and Mthwakazi People’s Congress (MPC).[32]

Vukani Mahlabezulu modelled itself as a radical cultural organisation focused more on revival of particularistic features of Ndebele culture and its main proponent was a novelist and academic, Mthandazo Ndema Ngwenya. He lost life in a mysterious car accident on the Bulawayo-Harare Road in 1991 together with another Ndebele-speaking academic known as Themba Nkabinde. Imbovane Yamahlabezulu was a radical pressure group that opened debates on the sensitive issue of the Fifth Brigade, putting pressure on the ZANU-PF government to be taken to account for the atrocities. The pressure group organised rallies and meetings where such political figures as Enos Nkala and others like Joseph Msika were invited to explain to the people as to who gave the instructions for the atrocities. ZAPU 2000 was a belated attempt to revive ZAPU following the death of Joshua Nkomo in July 1999. Its focus was a repudiation of the Unity Accord which was interpreted as a surrender document that did not benefit the ordinary people of Matabeleland who suffered the consequences of ethnic violence. It attacked the former ZAPU elite for selling out the people of Matabeleland for personal interests.

Mthwakazi Action Group on Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in Matebeleland and Midlands and Mthwakazi People’s Congress were a Diaspora phenomenon. They campaigned for the atrocities committed by the Fifth Brigade to be internationally recognised as genocide and for those people including Mugabe to be prosecuted for this action. They also sought the establishment of an autonomous United Mthwakazi Republic (UMR) as the only way for the Ndebele people to realise self-determination.[33]

The embers of the Matabeleland problem also pulsated around the death of Joshua Nkomo in July 1999. Despite having joined ZANU-PF in 1987, Joshua Nkomo was still revered in Matabeleland as umdala wethu (our old man). Joshua Nkomo occupied a special place within Ndebele particularism and was persecuted for being a Ndebele leader for a long time. Nkomo himself provides details of his persecution by ZANU-PF in his autobiography.[34] During his burial at the Heroes Acre in Harare, a big delegation from Matabeleland and the Midlands regions came to pay their last respects. What distinguished the Matabeleland delegation was the persistent song-uNkomo wethu somlandela, yenu Nkomo wethu (We will follow our Nkomo where ever he goes). This was an old PF-ZAPU song of liberation that encapsulated the loyalty and confidence of ZAPU supporters in Joshua Nkomo’s leadership.[35]

In a purely hegemonic style, ZANU-PF competed with the people of Matabeleland over ownership of Joshua Nkomo. Robert Mugabe took advantage of his death to express some lukewarm regrets about the atrocities committed by the Fifth Brigade for the first time. He assured the people of Matabeleland that the Unity Accord would be respected. For the first time, Mugabe described the Fifth Brigade atrocities as having happened during ‘a moment of madness.'[36] Besides coming nearer to apologising for the atrocities, Mugabe posthumously, granted Nkomo the long contested title of ‘Father Zimbabwe,’ arguing that Nkomo was a national model and a supra-nationalist that embodied all the cultures of the country.[37] The editorial column of the Zimbabwe News, an official organ of ZANU-PF carried the following title: ‘Farewell Dear Father’ and the editorial partly read:

The death of Cde. Joshua Nkomo must give birth to national dedication to those ideals that made him a national hero. To act otherwise would be betrayal of not only Cde. Joshua Nkomo, but all those in whose footsteps he walked such as Ambuya Nehanda, Sekuru Kaguvi, uMzilikazi kaMatshobana, and Lobengula the Great.[38]

For the first time, the founders of the Ndebele state, Mzilikazi and Lobhengula were listed together with Shona national heroes, in a desperate attempt by ZANU-PF to keep the people of Matabeleland within the fold of their party and within the Shona imagined nation and state.[39]

In the midst of all this, the younger generation of Matabeleland politicians like the president of Imbovane Yamahlabezulu, the late Mr. Bekithemba John Sibindi, responded by repudiating the Unity Accord that was emphasised by Mugabe and calling for an apology from Mugabe and compensation for the people of Matabeleland.[40] The young generation of political activists in Matabeleland became even more sceptical of territorial nationalism as represented by ZANU-PF in the absence of Nkomo. The common perception that had developed in Matebeleland was that ZANU-PF is a tribal party that survived on tribalism and served the interests of one ethnic group. This is how some people put it:

ZANU-PF is a party that is founded on splitting Zimbabwe into tribal groupings, i.e. Shona and Ndebele, whereby Shonas must provide national leadership. ZANU-PF, usually referred to as ‘The Party,’ has always had in their leadership deck Shonas taking up key leadership positions with a lacing of Ndebele apologists making up the leadership elite numbers. The party had to enlist the services of Ndebele apologists to paint a picture of a government of national unity following the inconsequential ‘Unity Accord’ signed in December 1987. The Ndebele apologists were to behave like gagged guests at this party-‘make no key decisions and above all don’t raise questions about the development of the other half of the country.[41]

The violence of the 1980s continued to be a major issue in Matabeleland. Its embers influenced politicians like Jonathan Moyo to design a Gukurahundi National Memorial Bill that he sought to table in Zimbabwe Parliament as part of a closure on the atrocities that left the country divided on ethnic lines.[42] Justifying the need for a Gukurahundi National Memorial Bill, Jonathan Moyo noted that:

It remains indubitable that the wounds associated with the dark Gukurahundi period are still open and the scars still visible to the detriment of national cohesion, national unity. These open wounds and visible scars have diminished the prospects of enabling Zimbabweans to act with a common purpose and with shared aspirations on the basis of a common heritage regardless of ethnic origin.[43]

While some contemporary analysts think that Moyo was just using the atrocities to gain support in Matabeleland, the fact remained that the Gukurahundi atrocities have remained open for political mileage. The action of Moyo provoked some Matabeleland political gladiators like John Nkomo, Dumiso Dabengwa, and Joseph Msika from the old PF-ZAPU to also make comments on Gukurahundi for the first time since their party was swallowed by ZANU-PF in 1987.[44] This salience of the Matabeleland problem has led Khanyisela Moyo, a Zimbabwean lawyer to state that: ‘In my opinion, the Matabele question is critical and cannot be cursorily thrust aside. It should be subjected to an intellectual and candid debate.'[45] Since 2000, the embers of the Matabeleland problems became more prominent in the Diaspora than inside Zimbabwe. This was partly due to the fact that the Zimbabwe crisis that unfolded in 1997 had forced millions of people into the Diaspora and partly because of the lack of democratic spaces in Zimbabwe to practise alternative politics to ZANU-PF’s one party mentality.

Diaspora, Matebeleland question and cyberspace

As Zimbabwe descended deeper into crisis punctuated by violence and displacement, many people migrated to Botswana, South Africa, Britain and other far away countries. Some of the displaced individuals and groups from Matebeleland once in the Diaspora began to make sense of the crisis in Zimbabwe and their fate as a minority group. Unlimited access to the cyberspace enabled some young Matebele people to articulate aspects of the Matebeleland question without fear or favour. Radical irredentist and secessionist ideas emerged in the Diaspora and were articulated within the cyberspace. This culminated in the creation of a ‘virtual nation’ known as the United Mthwakazi Republic (UMR), complete with its own national flag and other ritualistic trappings of a real national formation such as radio station.

Ndebele speaking people were among the first crop of Zimbabweans to migrate out of Zimbabwe even before the collapse of the national economy in 2000. Gukurahundi violence forced some Ndebele speaking people to take refugee at Dukwe Camp in Botswana in the 1980s. Some were forced to take asylum in such countries as the United Kingdom, Canada and USA. Thus by 2000, there was already a sizeable number of what one can term ‘pre-2000 Ndebele Diasporic community.’ This Diasporic community was composed mainly by PF-ZAPU activists and ex-ZIPRA combatants who were targeted by the Fifth Brigade.[46] By 1983, even the ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo was driven into exile in Britain.[47] This earlier crop of Ndebele Diaspora particularly in the United Kingdom were better institutionalised and organised, having carried with them a strong sense of PF-ZAPU identity and Matabeleland nationalism. Some of these earlier groups have remained die-hard ZAPU at heart even in the absence of PF-ZAPU. They consistently tried to revive ZAPU as they did not recognize the legitimacy of the Unity Accord of 22 December 1987 that enabled ZANU-PF to swallow PF-ZAPU.[48]

As the Diaspora Ndebele emerged from a highly ethnicised environment in Zimbabwe one can easily understand why their politics soon took ethnic forms. The United Mthwakazi Republic (UMR), complete with a flag and a radio station emerged in the United Kingdom. If one opens the website, it becomes clear that this organisation was born out of grievance and resentment of Shona triumphalism, leading the Ndebele in the Diaspora to define all the problems affecting the people of Matabeleland in ethnic terms. Gukurahundi atrocities provided the background against which cyber politics of secession of Matabeleland and the Midlands from Zimbabwe formed itself. This is combined with mobilization and appropriation of the proud memory of pre-colonial Ndebele history as well as the recent sad memories of the Fifth Brigade atrocities.[49] A separate history was claimed together with the appropriation of Joshua Nkomo, ZAPU and ZIPRA as the property and heritage of the Ndebele. Mthwakazi proponents declared that:

For our part, for our present generation, this Zimbabwe, and any attempts to maintain it in any guise in future as a state that includes uMthwakazi, is as false as it is silly. It is only part of the grand illusion of the whole Zimbabwe project created in 1980…What we have is their Zimbabwe, of Shonas, and a fledging state for uMthwakazi which we have called UMR.[50]

One other key contour of Ndebele Diaspora identity was that those that were in South Africa were finding it very easy to claim Zulu as well as Xhosa identities. This was due to similarities in language and some elements of common history and common clan names. It became very difficult for South African police to distinguish these Ndebele people from South Africans of Nguni origin particularly. Others, who came from areas like Beitbridge and the southern part of Gwanda, integrated themselves easily with the Venda and Suthu speaking communities, again because of close linguistic factors.

Internally ethnicity continued to cause trouble within political parties with ripple effects on the Diaspora. The split of the MDC into two factions in 2005 immediately polarised supporters of MDC outside the country with many Ndebele-speaking ones opting for the MDC that was led by Welshman Ncube. This split affected MDC structures in Britain and South Africa. What became known as the Welshman Ncube faction was considered to be a Ndebele faction. The Tsvangirai faction was cast as a Shona faction. This was despite the fact that both factions retained both Ndebele and Shona supporters and leaders. Bringing in Arthur Mutambara as a compromise leader of the Bulawayo-based faction did not prevent its being defined in ethnic terms as a Ndebele faction.[51]

What is not clear though is how the radical Diaspora Ndebele secessionist politics is impinging on internal Matabeleland politics. Within Matebeleland there has been a strong support for MDC-T since 2000. The smaller MDC also made significant inroads into some constituencies during the 2008 harmonised elections. But ZANU-PF was rejected. The consistent Matebeleland vote for the opposition is commonly interpreted as a protest vote against ZANU-PF that authorised the Gukurahundi atrocities. Those voting for the opposition seem to still believe in territorial nationalism and that with the introduction of democracy and human rights, there is still possibility of peaceful coexistence of ethnicities and races.

But gradually the radical Ndebele Diaspora politics is also impinging on internal regional politics. Such organizations as the pressure group called Ibhetshu LikaZulu have imbibed radical secessionist ideas to the extent of trying to make separate celebrations of those people they considered to be heroes from the region during the Heroes Holidays. In 2009, Ibhetshu LikaZulu even celebrated such controversial figures as Gwesela and Gayigusu who were always in the press in the 1980s as notorious dissidents as a Matebele heroes.[52]

A close look at the politics of Matebeleland, reveals that a number of community activists and political leaders including the late Governor of Matebeleland North Welshman Mabhena and former ZANU-PF Politburo member Joshua Malinga, have complained about Matebeleland’s marginalization since 1980. The Ndebele people’s complaints about exclusion from the nation-state and domination by the numerically preponderant Shonas have been ignored by the central state. As a result, the people of Matebeleland not only continue to feel like second class citizens of Zimbabwe but also continue to seek alternative ways of redressing their political and economic grievances, with the younger generations increasingly calling for violence and secession to redress their plight. Their feelings of discontentment and frustration with the national politics of the day have been equally shared by the older generation of leaders.

Matebeleland has also been in the forefront of pushing the agenda of devolution of power in the recent constitutional outreach programme. But what is clear is that Matebeleland has successfully banished ZANU-PF from the region through consistent voting for the opposition since 2000. But ZANU-PF has consistently tried to use the Unity Accord as their bait to lure the people of Matabeleland into voting for it forgetting that this unity reminded the Ndebele of how they were brutalised and forced into being members of ZANU-PF after the death of thousands of Ndebele-speaking civilians. Joshua Nkomo’s legacy and his support for national unity were also used by ZANU-PF in its attempts to win votes in Matabeleland. But ZANU-PF has not been successful.

But a number of political activities have taken place in recent years in Matebeleland which indicate the increasing political assertiveness of the Ndebele-speaking people, particularly taking the form of resistance to imposed ideas from Harare. They quickly saw through how Nkomo’s legacy was being instrumentally used to capture the Matebeleland constituency. The recent walking out of the Unity Accord by some high-ranking Matabeleland politicians and the re-emergence of ZAPU in 2009 under the leadership of Dumiso Dabengwa, has however added a new dimension and, consequently, there is an observable process of re-aligning in the politics of ‘re-capturing’ Matebeleland.

The recent repudiation of the Unity Accord of 22 December 1987 by some high-ranking ZANU PF leaders from Matabeleland, such as Thenjiwe Lesabe, Cyril Ndebele and Dumiso Dabengwa, and their re-launching of ZAPU in 2009, is not only a big vote of no confidence in ZANU PF’s nation-building project but also a reflection of Matebeleland’s continual cry for recognition. The relaunched ZAPU under the leadership of Dabengwa seeks to reclaim its pre-1963 national resonance and representativity which it claims ZANU-PF has destroyed through ethnicisation and racialisation of national politics and development.

Current Matabeleland politics and forthcoming elections

Currently Matabeleland is showing increasingly ethnic and regional dynamics with ZAPU having been revived and positioning itself to claim its Matebeleland and Midlands support-base from both MDC political formations. At another level, ZAPU under the veteran nationalist Dumiso Dabengwa is trying to claim its pre-1963 national political resonance while at the same time trying to regain its Matebeleland constituency. ZAPU’s publicity secretary Methuseli Moyo has been dishing out mixed signals-at one level articulating purely Matebeleland regional issues and on the other projecting ZAPU as an authentic liberation movement with strong national credentials poised to replace ZANU-PF from power.[53]

The Matebeleland region is currently issuing mixed and complex political signals. These range from a new repertoire of secessionist and irredentist politics, to electoral unpredictability. The revival of ZAPU and re-organisation of the MDC under the leadership of Professor Welshman Ncube who, unlike Arthur Mutambara, is considered a politician from the Matebeleland and Midlands regions, have the potential to contribute to the intensification of electoral competition come new elections. There is even possibility of a new regional coalition being formed including ZAPU and MDC aimed at maximizing electoral success in Matabeleland and the Midlands regions. Already, some ZAPU officials have begun imploring the officials of the smaller faction of the Movement for Democratic Change to ‘surrender the cross’ and join ZAPU before the forthcoming elections.[54] Some civil society groups have also implored the two parties to unite so that they could enter the elections as a strong regional force.

There is an incipient ‘political scramble’ for Matebeleland from different political gladiators with MDC-T fighting to retain its electoral dominance that it has enjoyed since the split of 2005. Some ZANU PF party heavyweights from the Matabeleland region whose political grip has waned over the years, have also made known their intentions to contest and recapture parliamentary seats in the region in the forthcoming elections. More than any region in the country, this has raised the spectre of bruising plebiscitary battles. But there are some young Ndebele-speaking political activists who lump MDC-T together with ZANU-PF as political formations representing those regions inhabited by dominant Shona-speaking people rather than Matebeleland. To these young activists, the people of Matebeleland are just being used to propel MDC-T into power and once that is done Matabeleland would be forgotten and its marginalization will continue.[55]

But ZANU-PF too has not given up on making inroads into Matebeleland using those former ZAPU members who decided to remain in ZANU-PF at the time Dabengwa revived ZAPU. The politics that has developed around the statue of Nkomo is revealing. It is also widely believed that the recent Nkomo statue debacle is part of the continuum of the efforts to recapture Matebeleland using Nkomo’s legacy and through the symbolism of Nkomo as a form of appeasement. The statue project was however hit by bad political weather taking the form of opposition from the surviving Nkomo family members and other members of the Matebeleland region tired of being recipients of ideas imposed from Harare.

Beginning with the refusal by Welshman Mabhena to be buried at the Heroes Acre, there is increasing snubbing of directives from ZANU-PF and Harare. When the other veteran nationalist Thenjiwe Lesabe died, ZANU-PF avoided another snub by not considering her for heroine status, with Didymus Mutasa of ZANU-PF saying ‘we could not confer on her the national heroine, which was rightful status, because she was not consistent when she joined ZAPU led by Dabengwa.'[56] Lesabe had made it clear before her death that she did not want to be buried at Heroes Acre. But a third ‘snub’ came soon after. Cornius Nhloko hailing from Silobela in the Midlands and a former Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) intelligence chief died at the age of 63 during the same week of Lesabe’s death. ZANU-PF conferred him a national hero status but his family indicated that Nhloko had made it clear that he did not want to be buried at Heroes Acre. These ‘snubs’ reinforce the widespread criticism that National Heroes Acre has essentially become a ZANU-PF burial ground rather than a national shrine.[57]

The popular view is that the much talked about ‘forthcoming elections’ that President Mugabe said will be held in 2011, will be the possible decider of the decade-long presidential challenge between Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai and President Robert Mugabe. The Matabeleland strand clearly promises to be brewing an election within an election. It could as well be the deciding region, either through its use as a decoy by some parties and/or the division of votes among multiple parties scrambling for regional support. Matebeleland dynamics are as equally important to watch as the national focus on the Mugabe-Tsvangirai duet.

The Matebeleland question has continued to be felt throughout all aspects of national politics, and opposition parties like MDC and Mavambo have all struggled to deal with the issue. The MDC split of 2005, for instance, largely evolved around the question of Matebeleland and how to handle issues of regional and ethnic representation within the party.[58] Similarly, the split in Mavambo after its modest performance in the 2008 elections also had a lot to do with issues of Ndebele people’s ethnic and regional representation within the party and how the party’s policies dealt with issues of Matebeleland’s historic marginalization.

The Matebeleland question has continued to loom large in the MDC-T’s current internal politics, and the party has increasingly come under fire from its Matebeleland supporters for its alleged insensitivity to the problems of the region and its failure to come out with clear policies on ethnic power balancing as well as a concise justice and reconciliation framework that adequately deals with the Gukurahundi legacy. At the same time, there has also continued to be simmering ethnic and regional struggles within the Welshman Ncube-led MDC over how to handle the Matebeleland question. All these problems, in a way, indicate serious challenges in current approaches towards resolving the Matebeleland question.

Conclusion

Nowhere throughout Zimbabwe have feelings of exclusion and marginalization been felt more strongly than in Matebeleland. Since 1980, the ‘Matebeleland Question’ has continued to project dynamics that speak to the unexplored legacies of hegemonic politics and violence as modes of governance, decentralization and devolution of power, linguistic and cultural diversity, and perceptions and realities of regional marginalization. The failure by the central state to address all these issues satisfactorily has evoked different responses from the people on the ground. The responses have included intensified calls for devolution of power, regional and ethnic fundamentalism as well as secessionism. Today, Matebeleland has become a theatre of renewed and frenzied political interest and the centre of a potentially seismic shift. As captured by The Standard of 15 January 2011: ‘If developments over the past year are anything to go by, there is every reason to expect the region to play a leading role in influencing the political direction in Zimbabwe.'[59]

But what is this Matebeleland question? It can be best described as a multifaceted one. It is historical and political. It is old and new. It is a national question. Its roots are traceable to the pre-colonial, colonial and postcolonial periods. It is deeply lodged within the development of the idea of Zimbabwe itself. It is about nation-building and authentic subjects of the nation. It is about who is considered a Zimbabwean and who is not. It is about inclusion of ethnicities into a single nation. It is a challenge to ethno-nationalism. It is about the style of governance and inclusive citizenship. It is about fair exercise of power and tolerance of diversity. As such, its resolution is inevitably about rethinking nation-building, citizenship and belonging as well as sharing of resources and power configuration. To resolve it, there is need to re-visit the idea of Zimbabwe and to democratize it. ZANU-PF messed it up since its emergence in 1963. Its resolution needs genuine nationalists, not lip-service ones. It reveals the failures of nation-building. It indicates the limits of coercion as a lever of nation-building. It points to the limits of ethno-nationalism that masquerades as territorial nationalism. It cannot therefore be resolved simply by elections as elections have proven to be more of an ethnic census.

References

[1] E. Msindo, ‘Ethnicity in Matabeleland, Zimbabwe: A Study of Kalanga-Ndebele Relations, 1860s -1980s’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, Cambridge University, August 2004); E. Msindo, Ethnicity, not Class? The 1929 Bulawayo Faction Fights Reconsidered,’ in Journal of Southern African Studies, 32 (3), (Sept. 2006), pp. 430-476; E. Msindo, ‘Ethnicity and Nationalism in Urban Colonial Zimbabwe: Bulawayo, 1950 to 1963,’ in Journal of African History, 48 (2007), pp. 245-267.

[2] Msindo, ‘Ethnicity in Matebeleland, Zimbabwe.’ See also S. J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Do ‘Zimbabweans’ Exist? Trajectories of Nationalism, National Identity Formation and Crisis in a Postcolonial State, (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009).

[3] J. Muzondidya and S. J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘Echoing Silences’: Ethnicity in Postcolonial Zimbabwe, 1980-2007,’ in African Journal on conflict Resolution: Special Issue on Identity and Cultural Diversity in Conflict Resolution in Africa, 7 (2) (2007), pp. 257-297.

[4] M. Sithole, Zimbabwe: Struggles within the Struggle: Second Edition, (Harare: Rujeko Publishers, 1999). See also The Zimbabwean War of Liberation: Struggles within the Struggle,’ in Journal of Southern African Studies, XIV (ii) (1988), pp. 304-322 and D. Moore, ‘The Zimbabwe People’s Army: Strategic Innovation or More of the Same?’ in N. Bhebe and T. Ranger (eds.), Soldiers in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War, (London: James Currey, 1995), pp. 73-103.

[5] E. V. Masunungure, ‘Nation-Building, State-Building and Power Configuration in Zimbabwe,’ in Conflict Trends Magazine, 1 (2006), pp. 1-10.

[6] N. J. Kriger, Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe: Symbolic and Violent Politics, 1980-1987, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 75.

[7] Abrams, ‘Strategy of Domination: ZANU’s Use of Ethnic Conflict As a Means of Maintaining Political Control in Zimbabwe, 1982-2006,’ (Unpublished MA Thesis, Rutgers University 2005).

[8] D. Martin and Phyllis Johnson, The Struggle for Zimbabwe: The Chimurenga War, (Monthly Review, New York, 1981).

[9] Alexander, at al , Violence and Memory, p. 220.

[10] Ibid, see also T. Ranger, Voices from the Rocks: Nature, Culture and History of the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe, (Baobab, Harare, 1999), N. Bhebe and T. Ranger (eds.), Society in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War, and Soldiers in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War, (University of Zimbabwe Publications, Harare, 1995). See also E. M. Sibanda, The Zimbabwe African People’s Union, 1961-87: A Political History of Insurgency in Southern Rhodesia, (Africa World Press, Trenton, 2005).

[11] When Enos Nkala a ZANU-PF cabinet minister referred to Nkomo as the king of the Ndebele who needed to be crushed, he was recreating Ndebele particularism and reducing Nkomo to a tribal politician bent on destabilizing Zimbabwe.

[12] Sibanda, The Zimbabwe African People’s Union 1961-87, p. 243.

[13] These were what became known as Assembly Points at which ZANLA and ZIPRA were gathered before their integration into the new Zimbabwe National Army.

[14] Kriger, Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe, p. 74.

[15] The Herald, 7 November 1980.

[16] The Herald, 7 July 1980.

[17] The Herald, 4 July 1980.

[18] The Chronicle, 7 July 1980.

[19] Quoted in Kriger, Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe, p. 135.

[20] The squabbles between ZANU-PF and PF-ZAPU gave the apartheid South African state an opportunity to destabilise the country through infiltration of what became known as Super ZAPU who pretended to be fighting on behalf of PF-ZAPU and Joshua Nkomo. These forces were in reality agents of destabilisation like REMO of Mozambique and UNITA in Angola.

[21] Abrams, ‘Strategy of Domination: ZANU’s Use of Ethnic Conflict As a Means of Maintaining Political Control in Zimbabwe, 1982-2006,’ p. 24.

[22] At the passing-out for Fifth Brigade in December 1982, ex-ZANLA commander Perence Shiri today the commander of Zimbabwe Airforce reportedly told the members: that ‘From today onwards I want you to start dealing with dissidents. We have them at this parade…Wherever you meet them, deal with them and I do not want a report.’ In July 1982 the commander of 2:1 battalion told his soldiers who had been sent to Lupane to deal with dissidents that ‘We came to hunt dissidents…if we want to finish some dissidents, we must first finish those in the section. After that we go to the bush.’ These statement are quoted in Kriger, Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe, pp. 134-135.

[23] S. J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The Post-Colonial State and Matabeleland: Regional Perceptions of Civil-Military Relations, 1980-2002,’ in Williams, R. Cawthra, G. and Abrahams, D (eds.), Ourselves to Know: Civil Military-Relations and Defence Transformation in Southern Africa, (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2003). See also S. J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘Nationalist-Military Alliance and the Fate of Democracy in Zimbabwe,’ in African Journal on Conflict Resolution, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2006).

[24] CCJP and LRF, Breaking the Silence, Building True Peace: A Report on the Disturbances in Matabeleland and the Midlands, 1980-1989, (CCJP and LRF, Harare, 1997). See also Jocelyn Alexander, ‘Dissident Perspectives on Zimbabwe’s Post-Independence War,’ in Africa, Volume 86, No. 2, (1998), pp. 151-182 and Rohjolainen Yap, ‘Uprooting the Weeds: Power, Ethnicity and Violence in the Matabeleland Conflict, 1980-1987,’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2001).

[25] When Enos Nkala became the minister of home affairs, he made it clear that the Fifth Brigade was there to eliminate all those categories of people in Matabeleland and the Midlands. See Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The Post-Colonial State and Matabeleland,’ pp. 18-38.

[26] S. J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The Post-Colonial State and Matabeleland: Regional Perceptions of Civil-Military Relations, 1980-2002’ in R. Williams, G. Cawthra and D. Abrahams (eds.), Ourselves to Know: Civil-Military Relations and Defence Transformation in Southern Africa, (Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, 2003), pp. 17-38, Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP) and Legal Resources Foundation (LRF) Report, Breaking the Silence, Building True Peace: Report on the Disturbances in Matabeleland and the Midlands, 1980-1989, (CCJP & LRF, Harare, 1997), R. Webner, Tears of the Dead: The Social Biography of an African Family, (Baobab, Harare, 1992) and J. Alexander, J. McGregor and T. Ranger, Violence and Memory: One Hundred Years in the ‘Dark Forests’ of Matabeleland, (Weaver Press, Harare, 2000).

[27] Bjorn Lindgren, ‘The Politics of Identity and the Remembrance of Violence: Ethnicity and Gender at the Installation of a Female Chief in Zimbabwe,’ in Vigdis Broch-Due (Ed.), Violence and Belonging: The Quest for Identity in Post-Colonial Africa, (Routledge, London and New York, 2005, p. 158.

[28] Lindgren, ‘The Politics of Identity and the Remembrance of Violence,’ p. 158.

[29] In 2002, I carried out in-depth oral interviews in Bulawayo and Gweru about the Ndebele perceptions of the military and the results indicated that to the Ndebele, the military is a Shona manned institution ranged to kill those who are not Shona.

[30] For details on the Unity Accord see Willard Anasi Chiwewe, ‘Unity Negotiations,’ in C. S. Banana (ed.), Zimbabwe , 1890-1990: Turmoil and Tenacity, (The College Press, Harare, 1989).

[31] Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The Post-Colonial State and Matabeleland: Regional Perceptions of Civil Military Relations, 1980-2002.’

[32] These organizations came into being in the wake of the swallowing up of PF-ZAPU by ZANU-PF in 1987 and they tried to pick from where such other earlier Ndebele particularistic cultural organizations as Ndebele National Movement, Matebele Home Society and Mzilikazi Family Association that were decentred by the rise of mass nationalism.

[33] The emergence of these organizations may also be interpreted within the broader perspective of the rise of civil society at the end of the Cold War.

[34] J. Nkomo, Nkomo: The Story of My Life, (London, Methuen, 1984).

[35] I attended the burial of Joshua Nkomo and witnessed this myself in July 1999 while based in Harare.

[36] Mugabe said this at a memorial service for Joshua Nkomo on 1999.

[37] Zimbabwe News: ZANU-PF Official Organ, Volume 30, No.6, (July 1999).

[38] Ibid.

[39] S. J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘Fatherhood and Nationhood: Joshua Nkomo and the Re-imagination of the Zimbabwe Nation,’ in K. Z. Muchemwa and R. Muponde (eds.), Manning the Nation: Father Figures in Zimbabwean Literature and Society, (Weaver Press, Harare, 2007).

[40] Interview with Mr. Beithemba Sibindi, Craneborne, Harare, 22 July 1999.

[41] Ndaba Mabhena, ‘The Tribal Warlords that Rule Zimbabwe’ in http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/opinion64.12515.html

[42] Professor Jonathan Moyo was initially radically opposed to ZANU-PF and he surprised many people when he emerged in the political scene as Minister of Information and Publicity at the turn of the millennium. He surprised many again when Mugabe kicked him out of ZANU-PF in 2005. He is currently an independent MP for Tsholotsho constituency, but also back in the fold of Zanu PF and once again deploying his destructive politics on the national scene.

[43] Jonathan Moyo (Independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Tsholotsho), Gukurahundi National Memorial Bill, 2006.

[44] Some were of the opinion that old wounds must be allowed to heal and others were clearly not satisfied about the way this issue was handled by ZANU-PF politicians.

[45] Khanyisela Moyo, ‘Ndebeles, A Minority that Needs Protection,’ in http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/gukgenocide16.13763.html

[46] I have interviewed some people who have been in the Diaspora since the 1980s in the UK and in South Africa. A number of them identified themselves as ZAPU activists forced into exile by ZANU-PF violence, and they still exhibit nostalgia for ZAPU politics.

[47] The gravity of the situation even forced Dr Joshua Nkomo himself to flee into Botswana then into the UK as an exiled politician in 1983.

[48] In 2004, I met two men and a woman in central London who were introduced to me as members of ZAPU and they were coming from a ZAPU meeting above Thames River.

[49] Mthwakazi, ‘Zimbabwe: A Project for the Humiliation of Nkomo and Mthwakazi’ in http://www.mthwakazionline.org/nkomo2.asp

[50] Ibid.

[51] The Bulawayo based faction has some Ndebele and Shona leaders just like the Harare based faction.

[52] There is high possibility that both Gwesela and Gayigusu were pseudo-dissidents sponsored by the ZANU-PF government to implicate PF-ZAPU in the manufactured politics of dissidence aimed at destroying its liberation credentials and authorising and justifying deployment of the Fifth Brigade in Matebeleland and the Midlands regions.

[53] But Methuseli Moyo has been accused of being openly tribalist in some of his writings and of branding ZAPU as a regional Ndebele political formation.

[54] Methuseli Moyo made the call for ZAPU and MDC to work together in a coalition so as to maximize their electoral power in Matebeleland.

[55] These critical minds often refer to how Morgan Tsvangirai had appointed a Karanga dominated cabinet and Matabeleland was not well represented. It was only after a regional outcry that people like Gorden Moyo were invited into cabinet.

[56] Lebo Nkathazo, ‘ZANU-PF Suffers New Heroes Acre Snub,’ in Newzimbabwe.com, 18 February 2011.

[57] Ibid.

[58] The split in the MDC was caused by a multiplicity of causes including differences over strategy, leadership and management styles as well as accountability issues. However, the split was precipitated by conflicts rooted in regional and ethnic divisions. Tsvangirai and his group were strongly supported in Harare and other areas dominated by Shona-speaking groups, while the Ncube-Sibanda group was strongly supported in Bulawayo and other Ndebele speaking regions.

[59] ‘New Radical Movements Expose Tribal Fault lines’ in The Standard, Saturday 15 January 2011 in http://www.thestandard.co.zw/local/28093-new-radical-movements-expose-tribal-fault-line…

A very interesting analysis of the problems facing the Ndebele nation and the obstacles facing the Republic of Zimbabwe.

For those of us who are of the Shona persuasion, It is clear that for the Zimbabwe experiment to succeed, we must engage the other tribes of Zimbabwe, in an attempt to influence the implementation of the politics of inclusion.

However, before this discourse can be meaningful, the admission of our complacency in the Gukurahundi atrocities due to our silence could go a long way to heal the nation. We did not protest when the armed gangs of murderers (our sons), killed our neighbors and relatives. Honestly, how can we live with ourselves? We were co-conspirators in this because we allowed the rulers to go ahead because we did not protest. It was business as usual. Silence means consent or does it? Have we forgotten the slogans of the government? Killing our own became legitimatized.

Today all the Zimbabwean citizens have seen or felt the results which came about due to our silence when the ruling class was clearly on the wrong track. The criminalization of our fellow citizens in order for a one-party state to be realized by the 30 year old government and thus dividing our people, allowing the ruling class to destroy our livelihood and silence all opposition. We don not even know what democracy is anymore.

The evidence is around us for all to seen. We are a divided nation, a nation where the majority of us are paupers while a 10th of the population sits on most of nation’s wealth.

There has never been a nation in the world which has had so many of its citizens in exile(for whatever reason) in peacetime. I believe we are the first nation to loose the use of our own currency and revert to the use of other countries’ currencies. The nation was essentially built on the greed and the desire for total control by the powers that be.

If we are to rebuilt this house, mutual respect and accomodation of all citizens of Zimbabwe must be the order of the day. Free speech and respect for individual choices must be a natural right.

Good governance can only come about if we as citizens choose our leaders wisely. At the end of the day we have the future generations to work for.

Long live democracy! Long live the multi-party state. We may be different, but surely all human desires have a common ground.

My thanks too for an extremely interesting piece that has gone a long way towards filling a big gap in my understanding of the current political situation in Zimbabwe.

Dear Majaradini & Jon Lunn,

Thank you for your comments. I am happy if my article came nearer to highlighting some of the core issues pertaining to politics unfolding in Matabeleland. Indeed the Matebeleland question needs some very sober attention that does not simplistically dismissed it as a manifestation of ethnicity or tribalism, because ethnicity or tribalism are mere reflections of deep rooted issues. I think its not too late for all the peoples thrown by history to live together between the great Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers to re-visit the basis of co-existence. The ongoing constitution-making process was one opportunity that was messed up by partisan thinking. I agree with Majaradini that people need not to belong to one ethnic group for them to co-exist peacefully. What is needed most is tolerance of diversity, respect for difference, avoidance of hegemonic ideas and notions of forced monolithic unity issued from the high political tables. What is needed is equal treatment of all citizens. An ideology of inclusion of all people of different races, ethnicities, genders, religions and generations must be deliberately promoted

This is an excellent piece of academic work which will help in our struggle to establish lasting peace and justice in Matabeleland and Zimbabwe.

Thabang M. Nare

PA to the Minister of State Enterprises and Parastatals

Very reach in information will help my overoll understanding of problems facing Zimbabwean nation.